Australia's GDP growth slows in Q3 amid productivity and inflation challenges

Subscribe to Macro Musing

To stay up to date on the latest economic insights, subscribe to Macro Musing on LinkedIn.

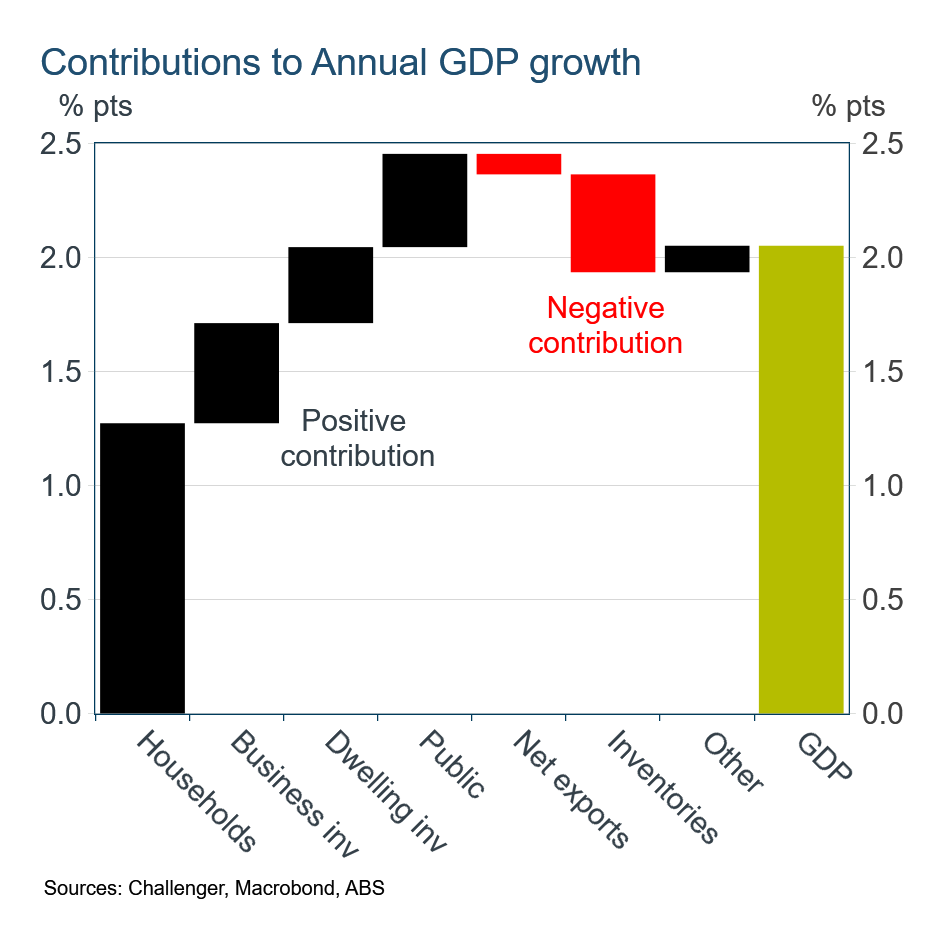

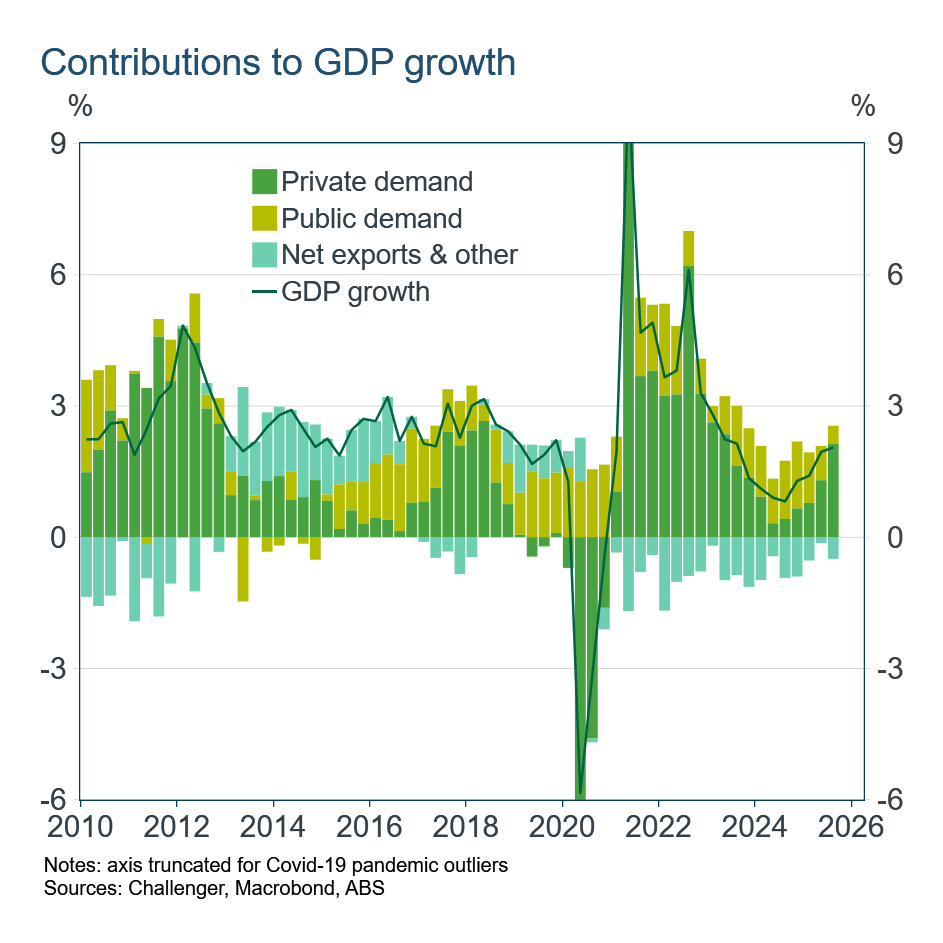

GDP grew 0.4% in the September quarter, and 2.1% over the year. In the quarter, stronger business investment and public spending were offset by inventories being run down (which subtracts from GDP growth).

There has been a clear pick-up in private demand, with GDP growth over the past year driven by household consumption and business and dwelling investment. The contribution of public spending to GDP growth has slowed with the ‘handover’ from public to private demand that the RBA has been waiting for finally here.

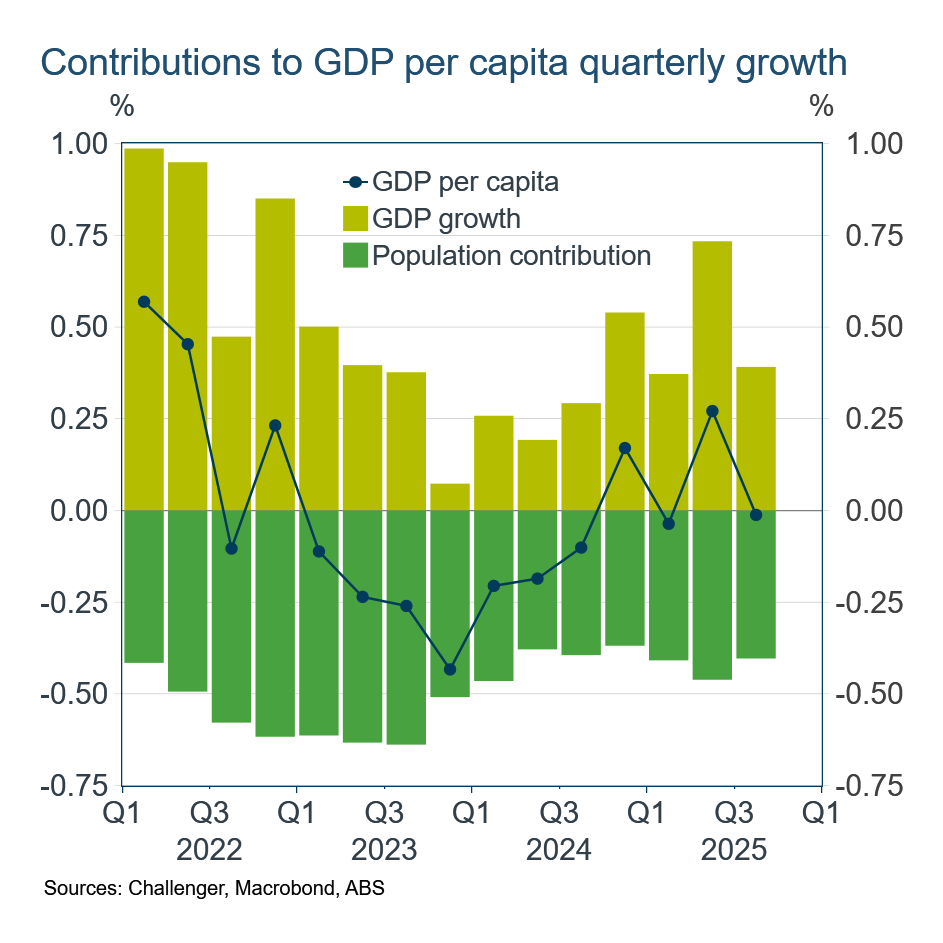

Growth of only 0.4% in the quarter matched steady population growth so there was no growth in GDP per capita in the quarter. Growth in GDP per capita has been improving but only very gradually, and it’s been a bumpy path.

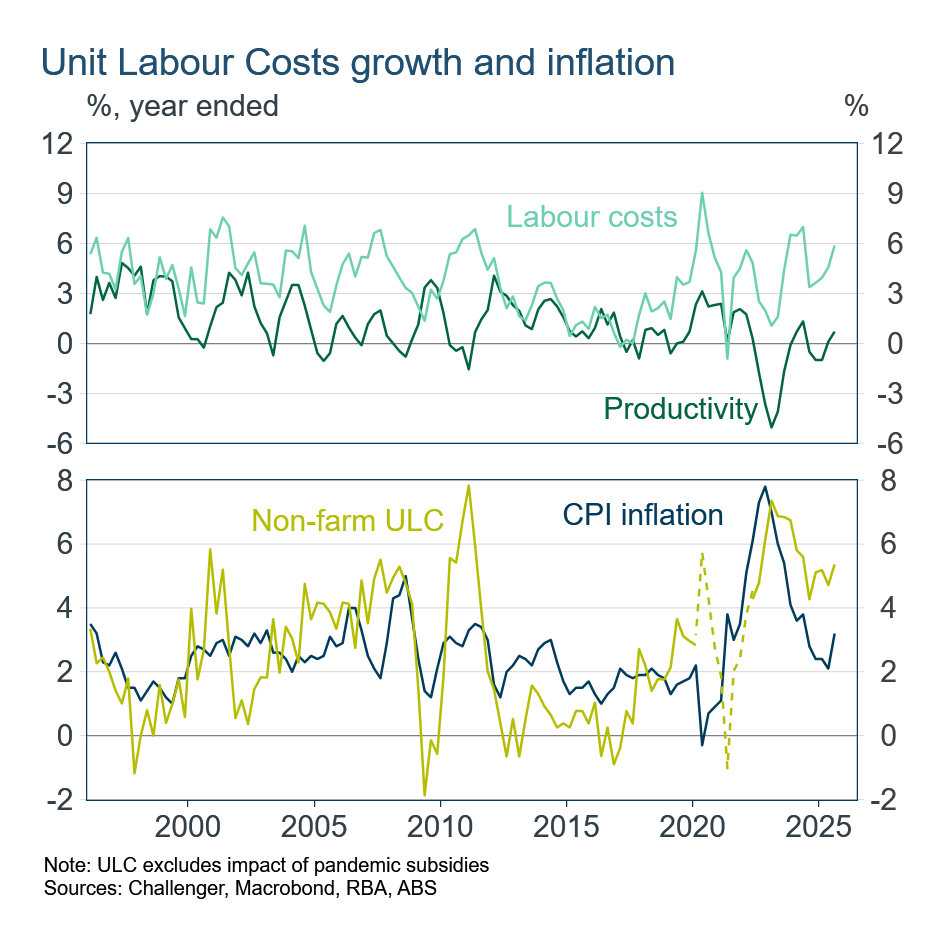

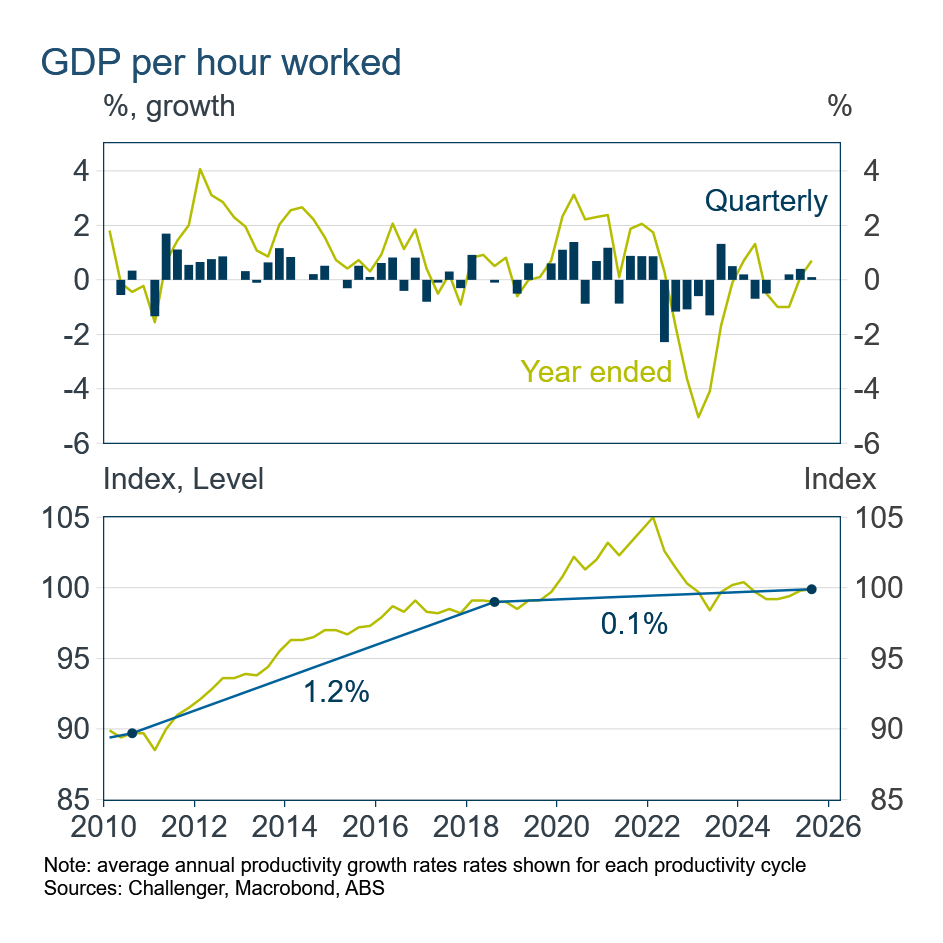

Dividing GDP by the number of hours worked, rather than population, gives the much discussed productivity. Everybody wants stronger productivity growth: the RBA wants it to contain inflation, and the Government wants it to lift living standards. Productivity growth (GDP per hour worked) was up 0.2% in the quarter and 0.8% over the year, around the RBA’s assumption for long-run productivity growth.

However, average annual productivity growth since before the pandemic has only been 0.1%. Large changes in employment and output through the pandemic created a lot of noise in measured productivity. The past two years since then suggest this 0.1% anaemic growth rate is the economy’s current trend rate of productivity growth.

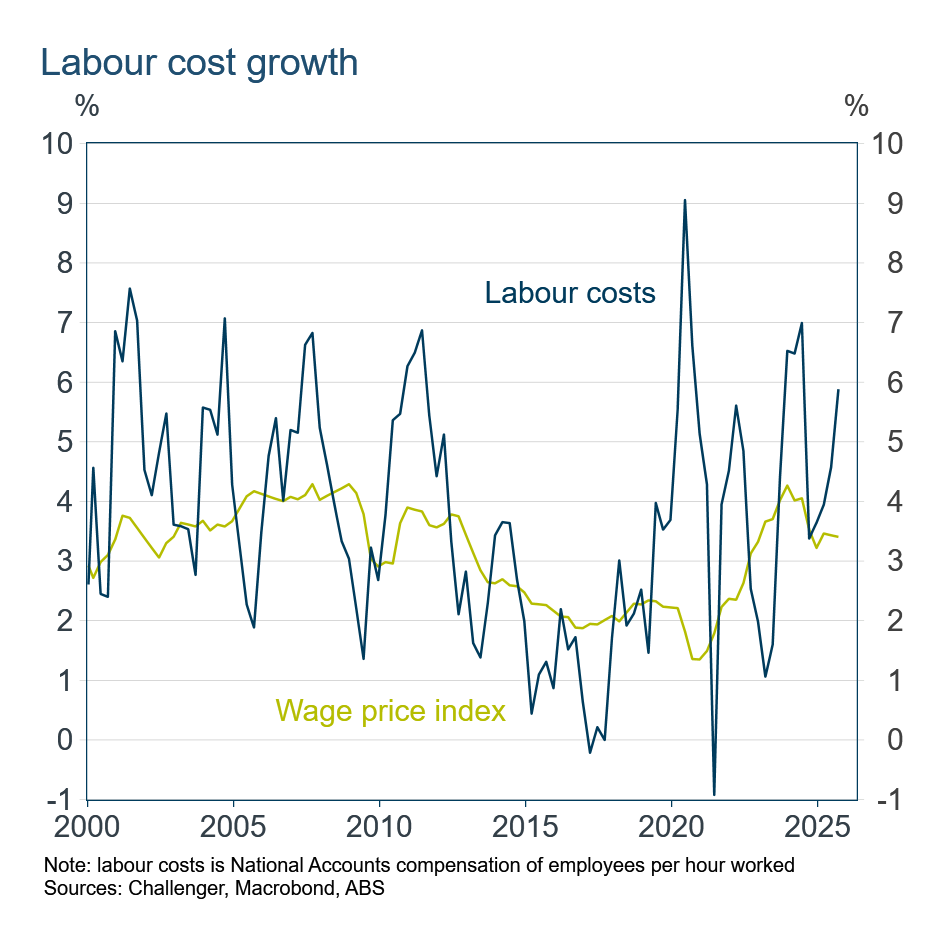

While highest profile measure of wages is the ABS’ Wage Price Index, that measures the increase in the wages for given jobs and does not include changes in other payments to workers or the increase in labour costs from changes in the mix of jobs (such as increased promotions, or higher salaries for new starters). Aggregate labour costs, which capture these other factors, have reported stronger growth, close to 6% and not much below recent peaks.

The challenge for the RBA is that with strong growth in labour costs, and weak productivity growth, unit labour costs are also growing very strongly. Unit labour costs growth is the best measure of the increase in businesses’ costs for a fixed amount of production, and so price pressures. The strong growth in unit labour costs will be making the RBA nervous about whether inflation really can return to its 2.5% target with the current policy setting. Overall, the September quarter National Accounts will have done little to put the RBA at ease.