Economic effects of Australia's migration and population growth

Subscribe to Macro Musing

To stay up to date on the latest economic insights, subscribe to Macro Musing on LinkedIn.

Migration has had a dominant role in Australia’s development, and debate has resurfaced on the impact of migration on population growth. The contribution of net migration to population growth surged after the pandemic however this reflects the pandemic impact on the timing of arrivals and departures. More generally net migration has been high for the past two decades. Migration generally has positive economic effects, but negative effects can be accentuated by year-to-year volatility in migration.

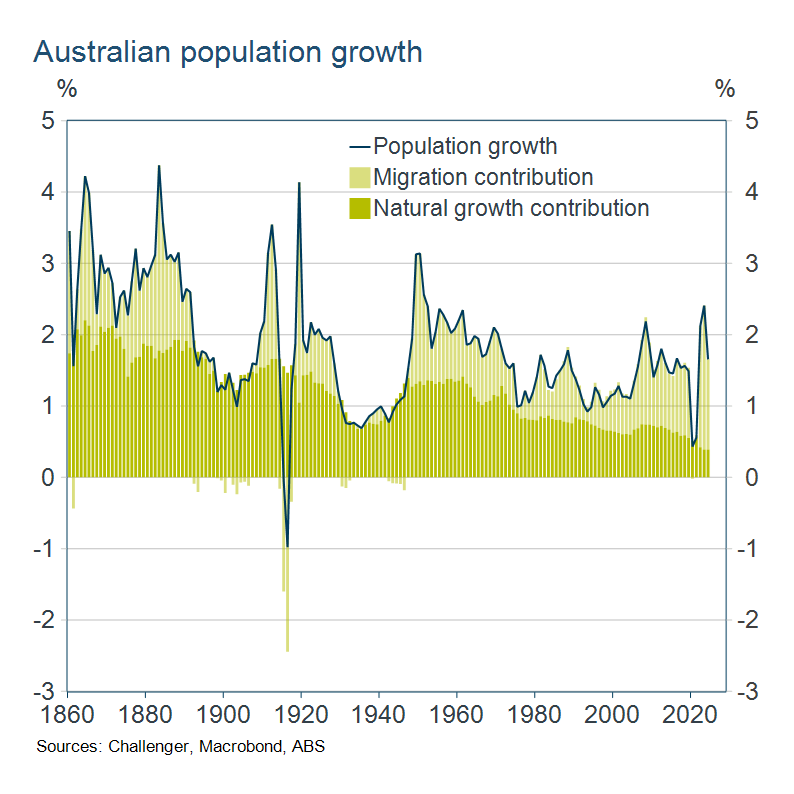

Australia’s population growth peaked at 2½% in 2023, the highest annual growth since the 1960s. While this peak was influenced by the pandemic as discussed below, the contribution to population growth from migration over the past decade has been strong, on par with the post WWII period. We have to go back as far as the 1860-1890 period to find consistently stronger contribution from migration to population growth.

As an aside, there have been several episodes when net migration was zero or even negative: the 1890s Depression, WWI, and the Great Depression and WWII period. The shocks that drive net migration to zero are obviously not desirable from an economic or welfare perspective.

Population growth from migration can’t be taken in isolation to the contribution from natural increase (births minus deaths). Migration can be a substitute for natural increase to maintain population growth. The contribution from natural increase has declined in an almost linear manner over the past 160 years, with some slight bumps relating to depressions and wars, falling from around 2 percentage points to less than 0.5 percentage points now.

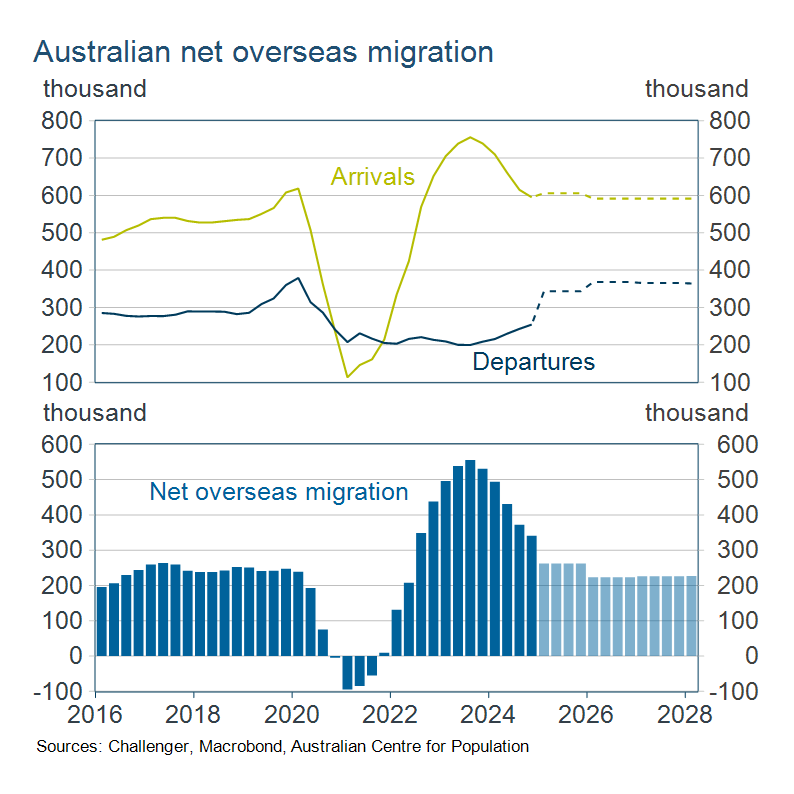

Net overseas migration counts the flow of non-Australians and Australians arriving in, or departing from, Australia for 12 months or more (within a 16-month period). In 2023 net migration doubled from its pre-Covid levels to peak at over 500,000 net arrivals. This contribution to population growth from migration in 2023 of 2 percentage points was the fourth highest contribution in over 160 years of annual data. However, this surge in net migration needs to be considered in the context of the collapse in migration in the preceding years as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Migration arrivals in 2023 peaked at just under 750,000, less than 150,000 higher than their pre-Covid peak. Almost as big a contribution to the net migration peak was that departures were lower than their pre-Covid norm by around 100,000. Departures were lower because there had been fewer arrivals, of students and those on working holidays etc, in the preceding years. In other words, the surge in net migration in 2023 was in effect payback for the collapse in net migration in 2020 to 2021.

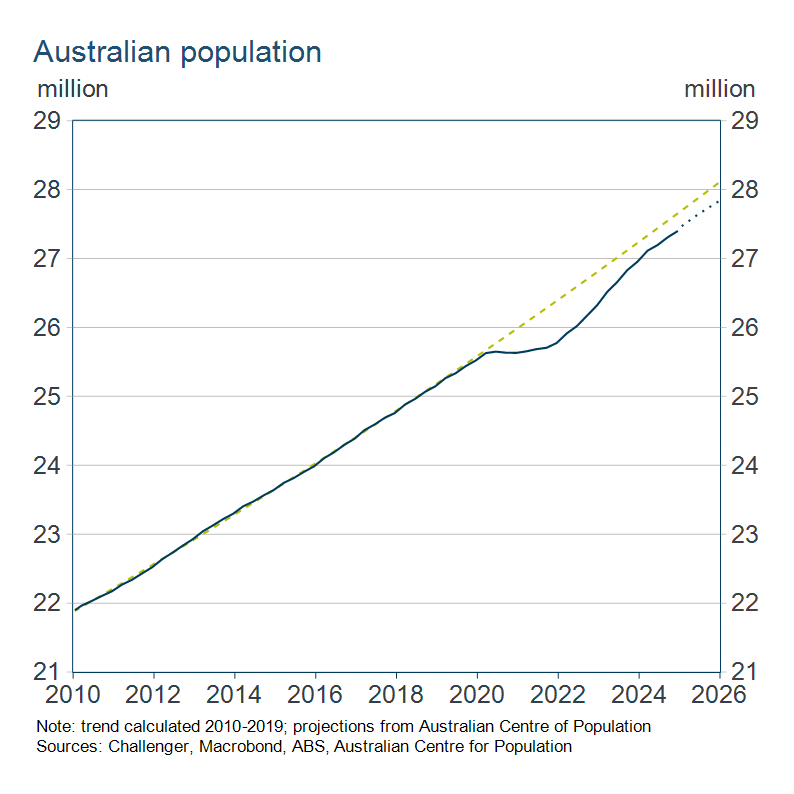

The net effect of lower arrivals, and later departures, is clear when looking at the level of the Australian population. Despite the spike in net migration and population growth in 2023, the Australian population has still not recovered to its pre-Covid trend.

Migration both influences economic conditions, and is influenced by economic conditions.

There is substantial research on the economic impacts of migration. Migration can temporarily reduce domestic wages due to increased supply of workers and also increases government spending. However, most studies find that immigration reduces unemployment for domestic workers. Beyond the impact on employment, evidence suggests that migration increases economic growth and productivity in the receiving country. The positive impact on growth is greater when migrants are highly skilled. The composition of migration will influence its economic impact and should be an important element of informed debate on migration.

Net migration is partly, but not completely, determined by the Government’s visa policies. Economic conditions in Australia relative to those abroad also contribute to net migration by influencing how many visa holders take up their visa, and whether they stay for the full length of their visa. Relative economic conditions also influence how many Australians leave the country for work and how long they stay.

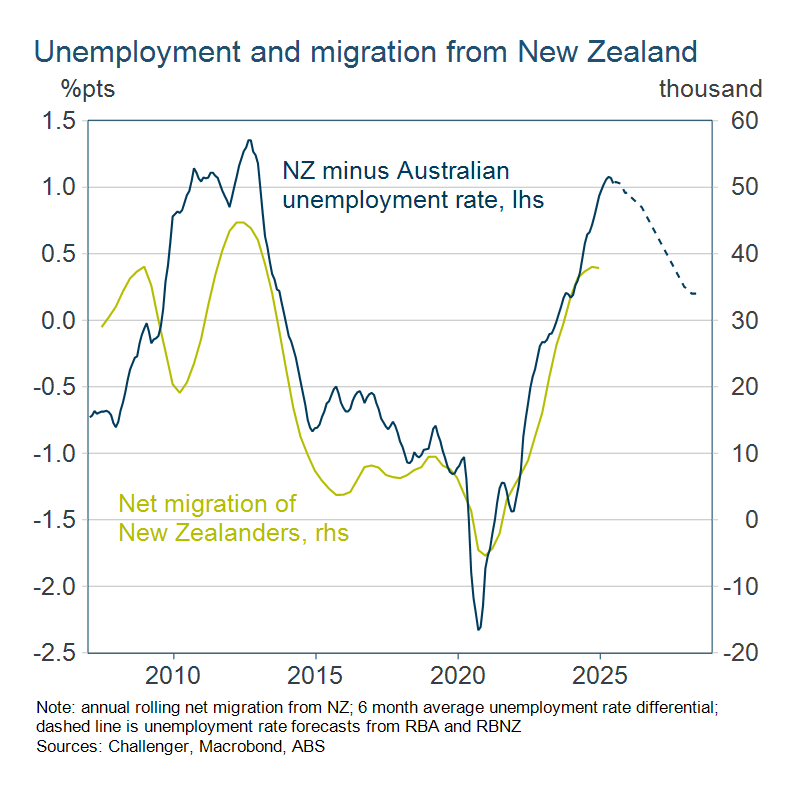

The impact of relative economic conditions on migration flows is clearly demonstrated for migration flows to and from New Zealand, where citizens can work in both countries without visas. Net migration from New Zealand closely follows the relative unemployment rates. The pick-up in net arrivals from New Zealand since the pandemic reflects Australia’s strong labour market, with the unemployment rate increasing only ¾ percentage point compared to 2 percentage points in New Zealand. With the gap between unemployment rates projected to fall, net migration is likely to decline.

The demand for housing is frequently a particular focus of the negative effects of immigration. However, while migrants do add to housing demand, they also add to housing supply, both as workers and because developers anticipate future demand, including from migrants, in deciding whether to commit to new projects. Unexpected changes in migration, from Covid-type shocks or abrupt changes in government policy, can then disrupt future housing supply and so may accentuate negative impacts from migration.

Ultimately the appropriate level of migration is a subjective decision for a country, but an informed debate always starts with good information. Migration policies are best being consistent, well-articulated, and clear in their objectives and impacts.