Diagnosing Australia's productivity malaise

Diagnosing Australia's productivity malaise

Download the article below.

Subscribe to Macro Musing

To stay up to date on the latest economic insights, subscribe to Macro Musing on LinkedIn.

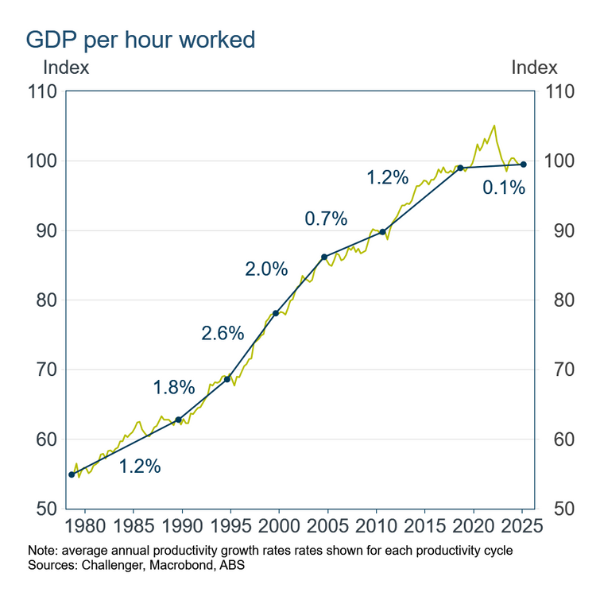

The Government is holding its "Economic Reform Roundtable" in response to no growth in productivity since before the pandemic. Over the period from 2018, annual growth of GDP per hour has averaged just 0.1%, well below earlier rates of 1-2% (Figure 1). Higher productivity growth is important for driving increasing living standards, increasing companies' future profits and asset prices, and lifting interest rates. Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman (1997) summed up that “productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run it is almost everything.”

Figure 1

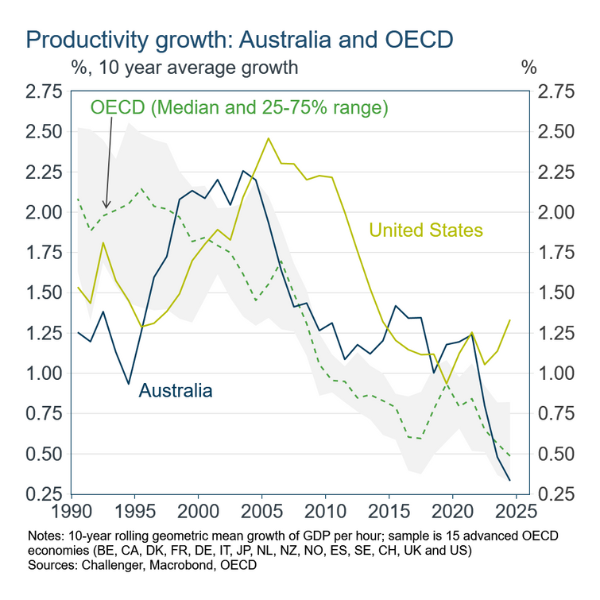

Figure 2

Slower productivity growth is (mostly) a global phenomenon

Across wealthy economies, productivity growth has been declining for decades (Figure 2). Several factors have driven this long-run structural trend.

- Deregulation and micro-economic reform boosted productivity growth in the 1970s through to the 1990s by removing impediments to business efficiency and so increasing the level, and so for a period of time the growth, of productivity. Reform, and so its productivity benefits, came later in Australian than in other parts of the OECD.

- Changing economic structure has reduced employment in manufacturing, which shifted to cheaper countries and tends to have higher productivity growth. Employment in service sectors, where (measured) productivity growth is lower, has also increased given the growth of incomes and aging in wealthy countries (e.g., health and social assistance services).

There is a long list of explanations for the slowdown in productivity. In Australia and internationally these include low R&D investment, declining business and market dynamism, slower uptake of new technology, slower growth of workers' skills, and increased regulation and barriers to competition.

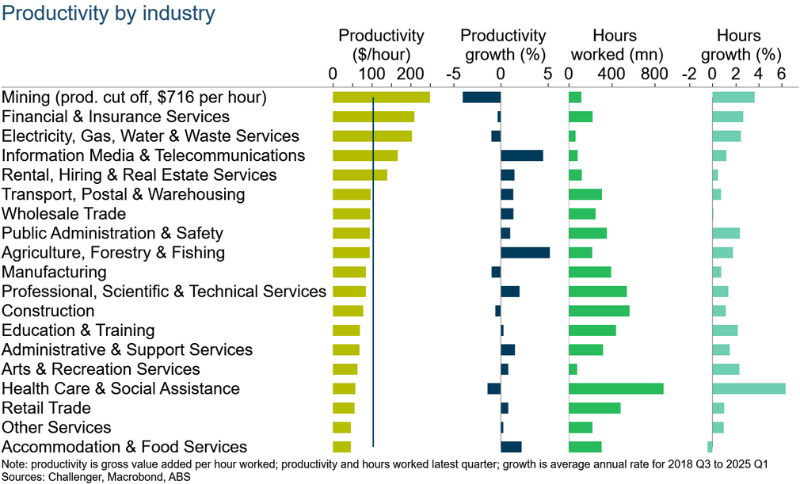

Productivity across industries

Productivity varies significantly across industries and jobs. It's highest in sectors that use more capital, particularly Mining which is very intensive in machinery and in Australia has productivity of over $700 per hour, seven times the economy-wide average (Figure 3: column 1). The lowest measured productivity is in a range of service industries: Accommodation & Food, Retail Trade, Health & Social Assistance, and Arts & Recreation. Over the past seven years, productivity growth has been weak across most industries.

The total amount of employment is greater in industries with lower productivity (particularly Health Care & Social Assistance Retail Trade, and Construction) (Figure 3: column 3). The industries with the highest productivity, not coincidentally, have lower employment as fewer workers are needed because of the high productivity. The more productive a sector becomes the fewer workers are needed and so the less it contributes to aggregate productivity.

Strong employment growth in the low-productivity Health Care & Social Assistance industry has led to suggestions this is driving Australia's weak productivity.

Figure 3

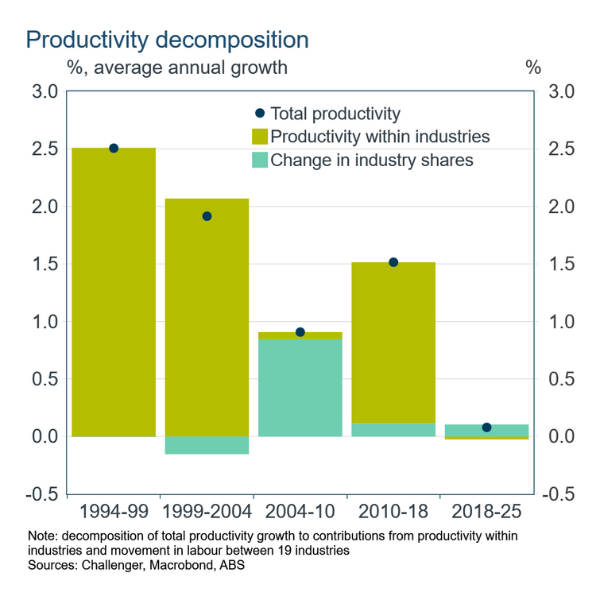

Decomposing the industry effects of productivity growth

Decomposing the impact of changing employment shares at the industry level provides important insights (Figure 4). In the period 2018 to 2025 changes in employment shares across industries added 0.1% to aggregate productivity growth. While employment grew in some low-productivity industries, proportionately it increased more in some higher-productivity industries. Productivity growth within each industry contributed absolutely nothing to economy-wide productivity growth. Our weak economy-wide productivity results from low productivity growth in almost all industries, not an increase in employment in low-productivity industries.

Note that in 2004 to 2010 the mining boom saw the share of Mining employment increase from 1% to 1.6%. Because the level of productivity in Mining at the time was over ten times the level in the rest of the economy the increase in mining employment significantly contributed to higher economy-wide productivity.

Comparing our productivity growth to the United States

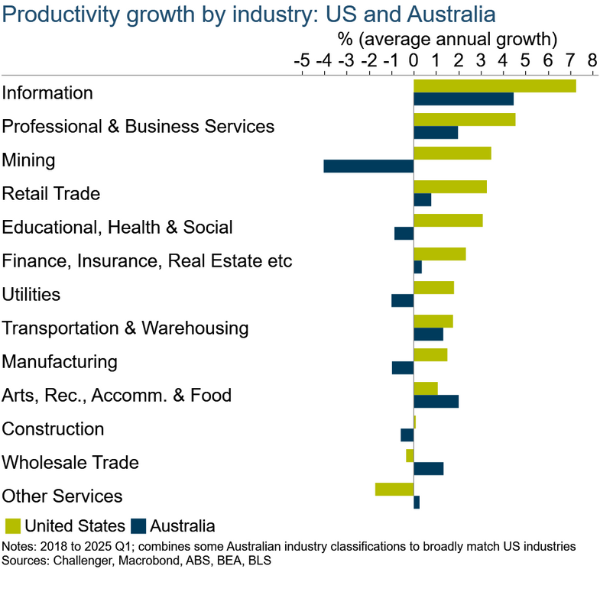

In the United States productivity growth has remained strong over the past decade. A comparison across industries demonstrates that productivity growth has been weak across the board in Australia (Figure 5; note this is a comparison of the growth of productivity, not the level of productivity, which is also higher in the United States). The strength of US productivity growth across all industries relative to Australia indicates that advancement in technology, the ultimate driver of productivity, can overcome structural factors constraining aggregate productivity, such as changes in the structure of the economy. Indeed, the stronger US productivity across industries and the slowdown in Australian productivity growth across most industries suggests that there are economy-wide factors constraining productivity in Australia.

The cause and effects of Australia's weak productivity

Productivity growth is always seen as a good thing. When was the last time you heard a politician or business leader call for lower productivity? If it was easy to identify ways to increase productivity we would have already done so. Most productivity growth comes from the private sector which employs 80% of people. But government regulations set the environment in which private companies operate and so influence productivity growth.

Looking for economy-wide constraints to productivity, one contender is regulation. It is hard to point to specific regulation that might be hampering productivity, the cumulative impact and interaction of individual seemingly innocuous regulations may be significant. While the reforms of the 1980s and 1990s were widely accepted to be removing impediments to growth, today one person's reform can often be another's regulation. Regulations that have benefits for the environment, the structure of our cities or workers' conditions can be positive but we should also be realistic if they constrain productivity and consider that trade-off. However, stronger productivity growth may not be worth it if the social costs are too great. No doubt there will be many perspectives at the Government's Economic Reform Roundtable.

Related content

Stay informed

Sign up to our free monthly adviser newsletter, Tech news containing the latest technical articles, economic updates, retirement insights, product news and events.