Macro Musing: RBA: should it stay or should it go (25bps)?

Subscribe to Macro Musing

To stay up to date on the latest economic insights, subscribe to Macro Musing on LinkedIn.

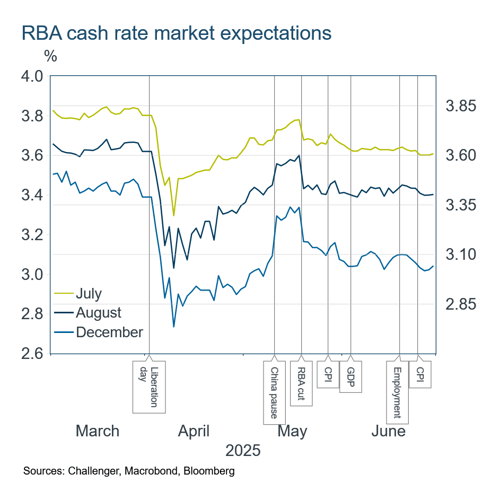

An RBA rate cut to 3.6% next week is almost fully priced by financial markets. Indeed, markets expect at least three cuts by year end, to less than 3.1%, compared to March pricing for less than two cuts. This is a sharper pace of cutting than expected in peer economies. That does not seem justified given the economic outlook.

It hasn’t been weaker domestic economic data that has driven this reassessment since March. The biggest mover of rate expectations was President Trump’s April tariff announcement, and then winding back of tariff expectations leading up to the 12 May pause of tariffs on China.

The only domestic news that’s significantly moved rate expectations was the RBA’s May rate cut, which markets interpreted as dovish. But the RBA communication at that time was that it projected it would get close to its inflation and (un)employment targets with two cuts this year, not three. Rate expectations have barely moved with major data release – GDP, employment and two monthly CPI data releases – since then.

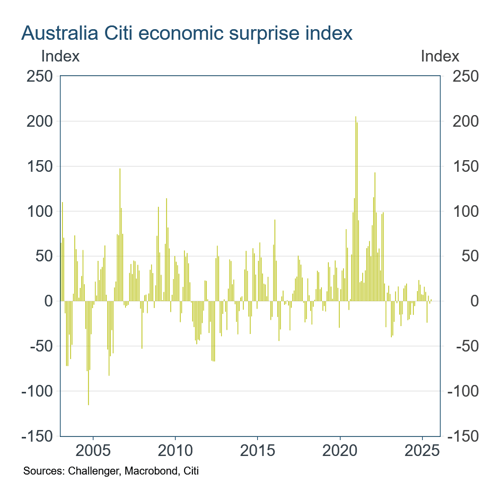

A key explanation for rate expectations not moving with data releases is that data haven’t been surprising, in other words releases didn’t contain ‘news’. This is seen in the fairly small values of the Citi economic surprise index. But this index only measures the surprise in the data release relative to the expectation just before the release, not the gradual evolution of expectations in say the month leading up to a data release.

Often too much focus is given to ‘news’ not the slow accumulation of evidence. In other words, it’s important to also look at the level and not just the change.

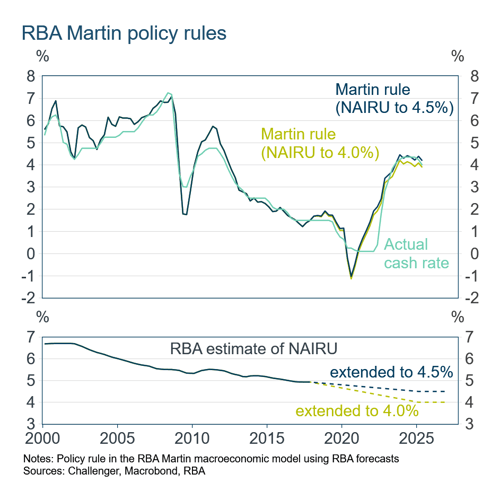

One way we can do this is with ‘policy rules’ (sometimes called ‘Taylor rules’). These rules say what the cash rate ‘should’ be based on economic data (or forecasts), or at least what cash rate would be consistent with how the RBA has previously set policy. The rule in the RBA’s MARTIN economic model relates the cash rate to the RBA’s key targets the inflation rate and unemployment rate. Modifying this rule to use the RBA’s forecasts of inflation and unemployment explains the history of the cash rate very well (albeit the actual cash rate has smaller extremes, suggesting the RBA is a bit more cautious).

One important input into this rule is the NAIRU, the ‘non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment’. The NAIRU is the unemployment rate that would keep inflation stable, neither increasing or falling. It can’t be observed and has to be estimated. The RBA’s estimate declined in the years up to the pandemic. The RBA has said that they believe the NAIRU had declined further and is now around 4.5%. Others have suggested the sharp slowing in wages growth with only a very small increase in the unemployment rate indicates the NAIRU is lower, perhaps around 4%.

The NAIRU estimate is particularly important for thinking about what the cash rate should be now. If you believe the NAIRU has fallen to 4%, then the cash rate should be under 4%. But if the RBA is right and the NAIRU is higher, then a cash rate just over 4% is appropriate.

Unfortunately, even the RBA seems uncertain about where the NAIRU is and we haven’t had formal updates from the RBA on its estimates of the NAIRU.

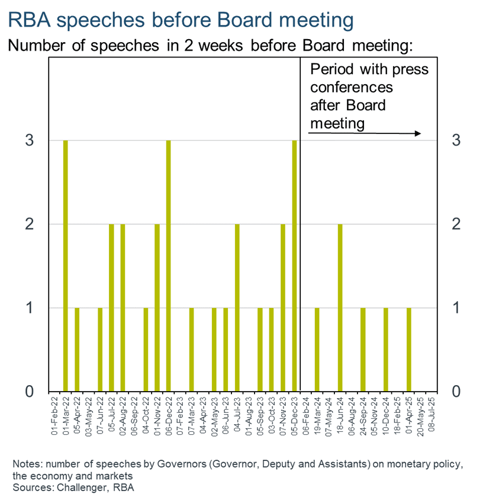

The RBA’s communication has changed since the recommendations in the 2023 RBA Review. The RBA Governors still give roughly the same number of speeches on the economy and monetary policy (46 in 2024 vs 43 in 2022, headed to 36 in 2025 vs 38 in 2023). However, this includes the RBA Governor’s press conferences which occur after each Board meeting. The RBA is communicating more in explaining its decisions, but giving fewer speeches explaining the RBA’s thinking on the structure of the economy, such as how and why the NAIRU is evolving.

The timing of RBA communication has changed also. Notably, there are fewer speeches in the two weeks preceding the RBA’s Board meeting. This gives the RBA fewer opportunities to guide market thinking in a turbulent environment.

It’s clear the RBA will be cutting rates this year, the uncertainty is when and how quickly. Given market pricing is so firm on a cut in July, and the RBA hasn’t guided the market away from this view, it’s likely the RBA will cut 25 basis points next week. However, it should be a hawkish cut, providing guidance that the economic outlook does not justify an additional two cuts this year.