Money, money, money...tariffs downside with little upside

Subscribe to Macro Musing

To stay up to date on the latest economic insights, subscribe to Macro Musing on LinkedIn.

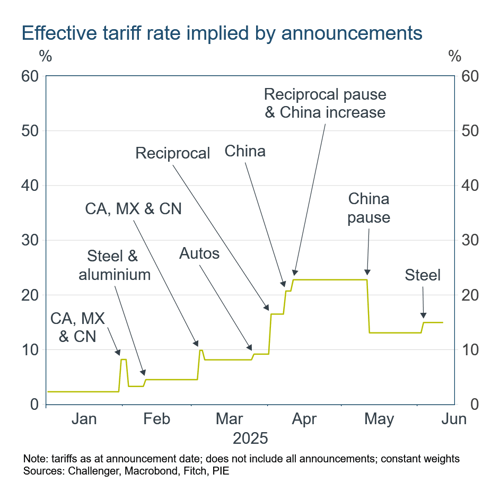

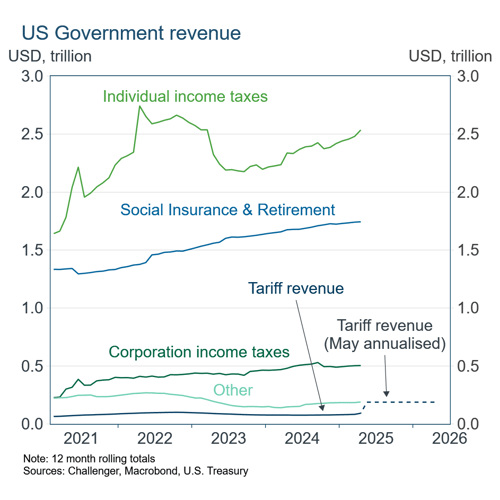

After a period of relative quiet on tariff announcements, President Trump doubled the tariff on steel imports to 50% in early June. This lifted the implied effective tariff rate in the United States to around 15%, based on the composition of imports in 2024. However, tariff revenue collected has been much less than announced tariffs would suggest, worsening the US fiscal outlook.

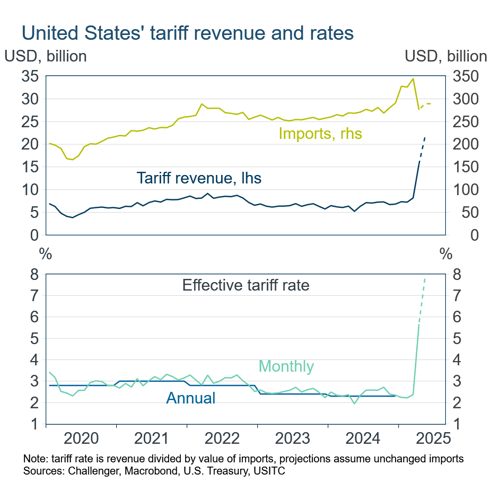

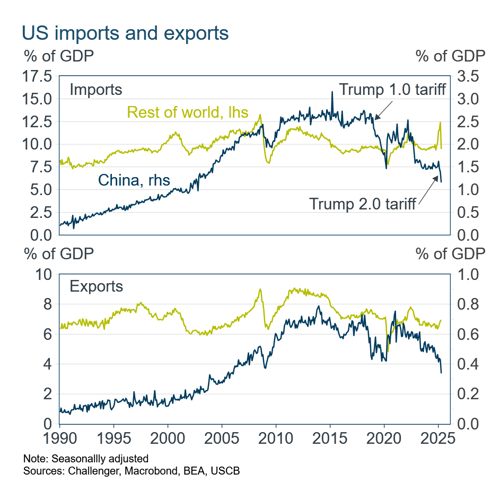

Imports into the US surged early this year as companies acted to get ahead of higher tariffs. Tariff revenue has jumped from around $8 billion per month last year to a projected $22 billion in May. Based on the value of imports, this implies the average effective tariff rate in May was around 8%.

This is significantly less than announced tariffs (aggregated above using the composition of imports in 2024). The explanation it seems is that businesses respond to higher prices, with the composition of imports shifting to goods with tariff exemptions or lower rates. In part this has been facilitated by the bring forward of imports before higher tariffs were imposed. With time, imports will resume for some of these higher tariffed goods resulting in further increases in revenue and effective tariffs.

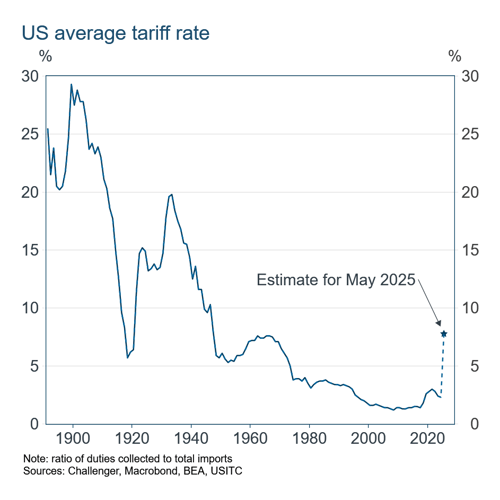

This estimate for May brings the average tariff rate in the United States back to around its 1960s levels, much less than suggestions that average tariff rates are around the rates of the early 1900s. This hides some of the damage tariffs are doing to the economy by effectively pricing some imports out of the United States.

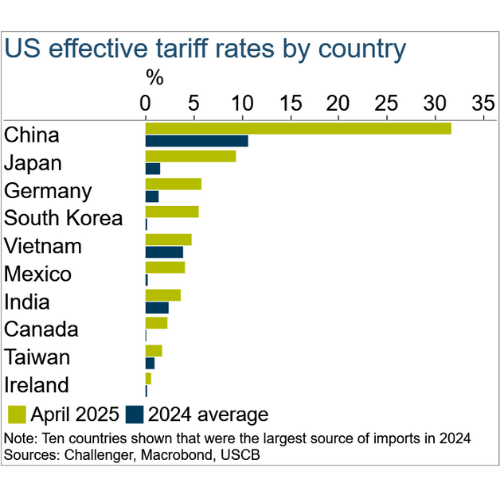

Based on tariff revenue data for April, the highest average effective tariff has been on imports from China, at over 30%, with substantial increases also for Japan, Germany and South Korea. Effective tariff rates on Canada and Mexico are lower, despite them both notionally facing 25% tariffs, as many of their exports to the United States are exempt from tariffs under the existing free trade agreement between those countries.

With China facing a much higher tariff, not surprisingly, imports from China have experienced a significantly larger sustained fall than those from other countries. However, the fall in imports from China this time has to date been smaller than the decline from a smaller increase in tariffs in the first Trump administration. This suggests Chinese imports will decline further.

The other implication of imports shifting away from higher-tariff goods is that the US Government will raise less revenue. If tariff collections continue at the rate seen in May, annual tariff revenue will triple to around $200 billion. While this might seem substantial it is still much less than the estimated $557 billion annual cost of the tax cuts in President Trump’s ‘Big Beautiful Bill’. This reinforces that US deficits and debt issuance will continue to grow, placing upward pressure on US long interest rates.

Related content

Stay informed

Sign up to our free monthly adviser newsletter, Tech news containing the latest technical articles, economic updates, retirement insights, product news and events.