Defence spending: the only way is up

Subscribe to Macro Musing

To stay up to date on the latest economic insights, subscribe to Macro Musing on LinkedIn.

At the NATO summit currently underway at the Hague, members are expected to formally agree to increase defence spending to 5% of GDP, a target proposed by President Trump. While some countries have significantly increased defence spending almost all are well behind this new target. With Government budgets already under pressure, raising taxes or cutting spending will be politically difficult, and so a substantial increase in defence spending will almost certainly add to already high government debt, pushing government yields higher.

NATO members have reportedly agreed to reach the 5% target by 2035 after Spain obtained an exemption. The NATO secretary general has proposed the 5% target could be met with 3.5% of core defence spending and 1.5% of GDP on “defence and security-related investment, including infrastructure and resilience”. Countries on the east of Europe wanted an earlier target.

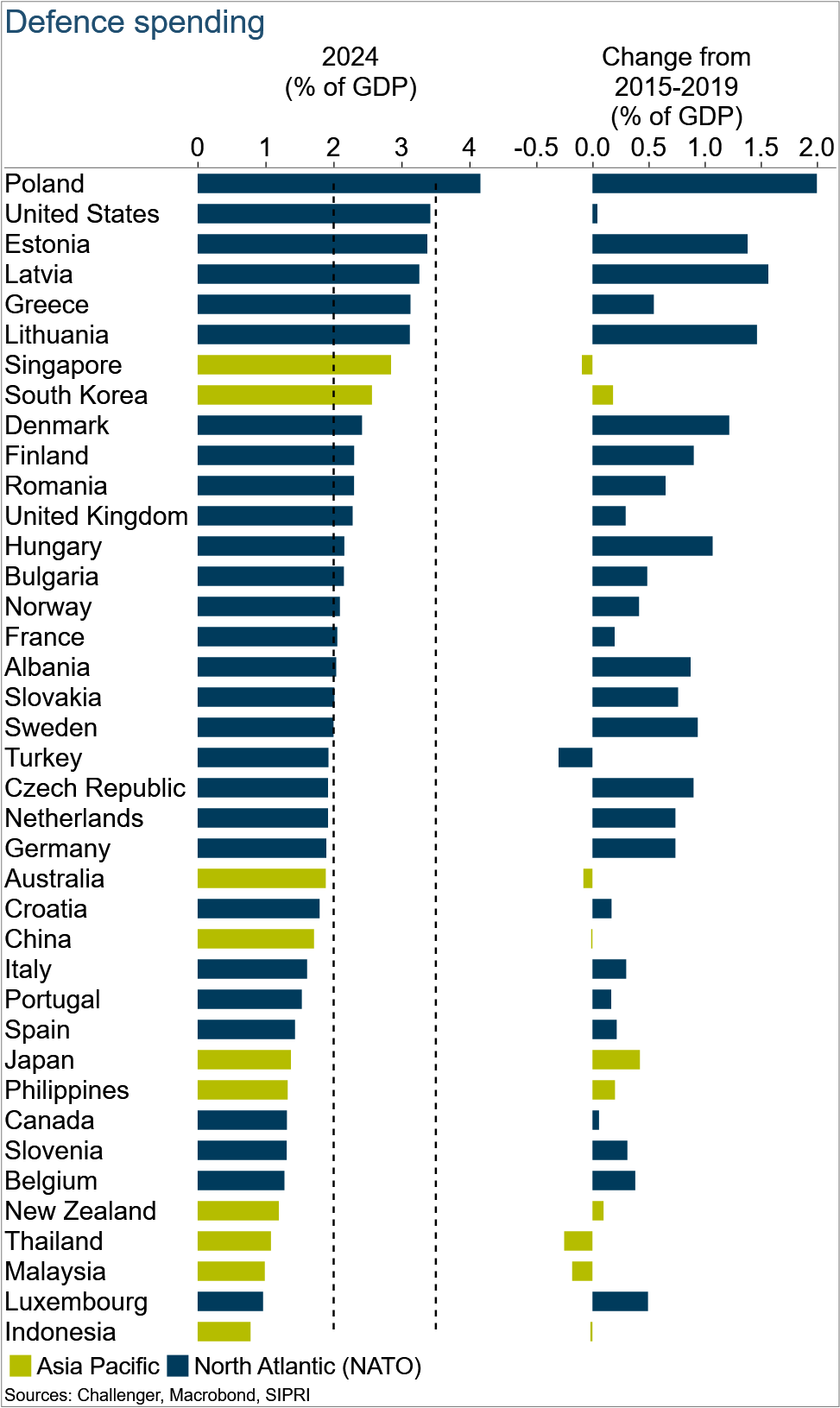

There have already been large increases in defence spending by countries in the east and north of Europe after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Defence spending increased by 2% of GDP in Poland, by 1.5% of GDP in the Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania), and by around 1% of GDP in northern Europe (Denmark, Finland and Sweden) and central Europe (Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia).

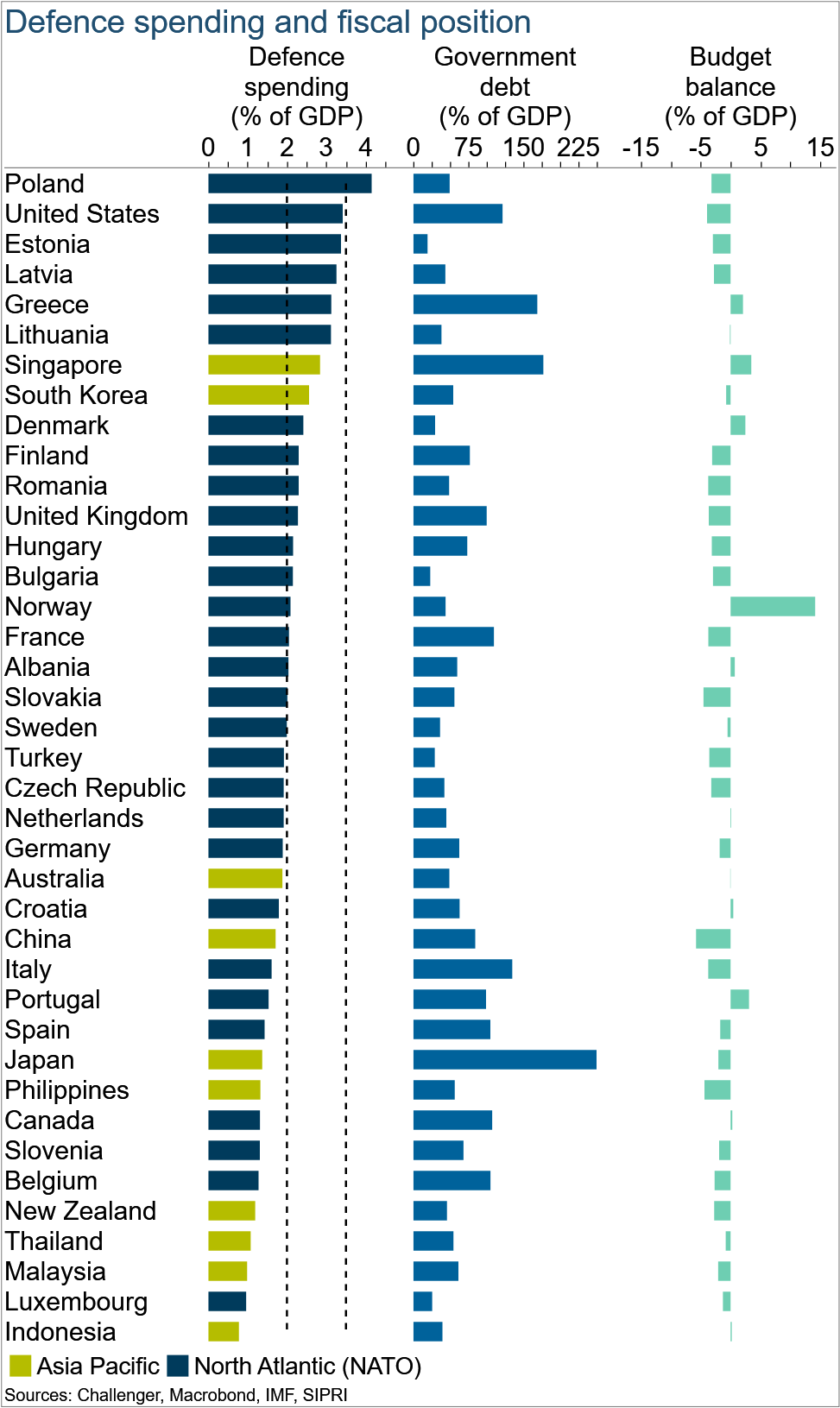

However, even after this big increase, only two-thirds of NATO members meet the 2% of GDP target that was set a decade ago. Canada is a long way from even the previous target having committed to reach 2% of GDP by 2032, up from 1.4% of GDP this year. Further big increases in spending will be needed by many countries.

Increased defence spending will add to fiscal pressure for the many European countries that already have significant budget deficits and high debt. France, Italy, and Spain – and Canada – will all have to increase defence spending by 1.5 to 2% of GDP and already have Government debt of 100% of GDP or more and most have fiscal deficits.

Even Germany, where Government debt is lower at 60% of GDP, plans to borrow €400 billion to reach the target which will have it spending over €150 billion on defence by 2029.

The increase in sovereign debt will push yields higher. At least the good news is that defence spending has a stimulatory impact on the local economy and will benefit defence companies. And higher defence spending could potentially prevent a wider war with Russia in Europe that has been estimated could cost the world $1.5 trillion dollars.

Countries in the Asia Pacific do not have a formal defence pact with spending targets, and with the exception of Korea and Singapore defence spending is much less than in NATO countries.

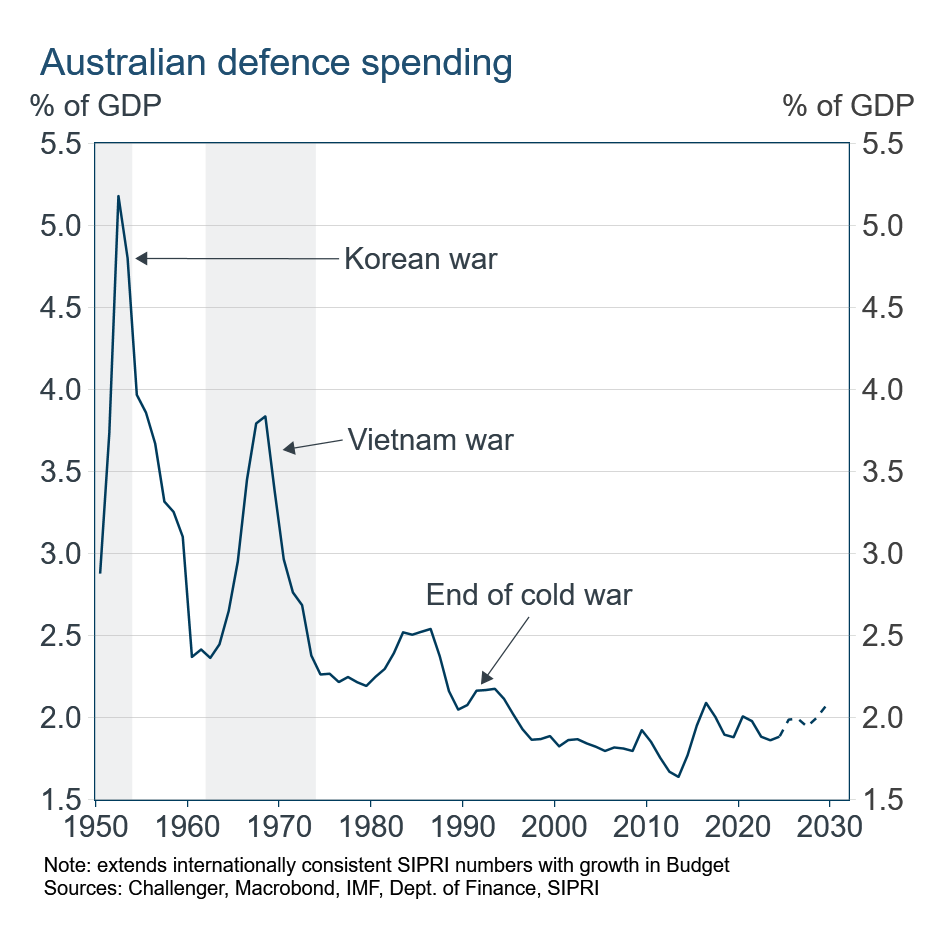

United States defence secretary, Pete Hegseth, called on Australia to lift defence spending to 3.5% of GDP, adding $40 billion per year to Australia’s defence spending. However, the Australian Government has pushed back on a what would be very big increase in defence spending for Australia. Australia’s defence spending has been mostly below 2% of GDP since the end of the cold war, and was only consistently above 2.5% of GDP around the Korean and Vietnam wars.

However, it remains possible, or even likely, that increases in Australia’s defence spending could feature in tariff negotiations with the United States. Increased defence spending would add to Australia’s 2% of GDP structural budget deficit which already requires fiscal belt tightening, putting upward pressure on bond yields.