Persistent inflation delays rate cuts, RBA's challenges ahead

Subscribe to Macro Musing

To stay up to date on the latest economic insights, subscribe to Macro Musing on LinkedIn.

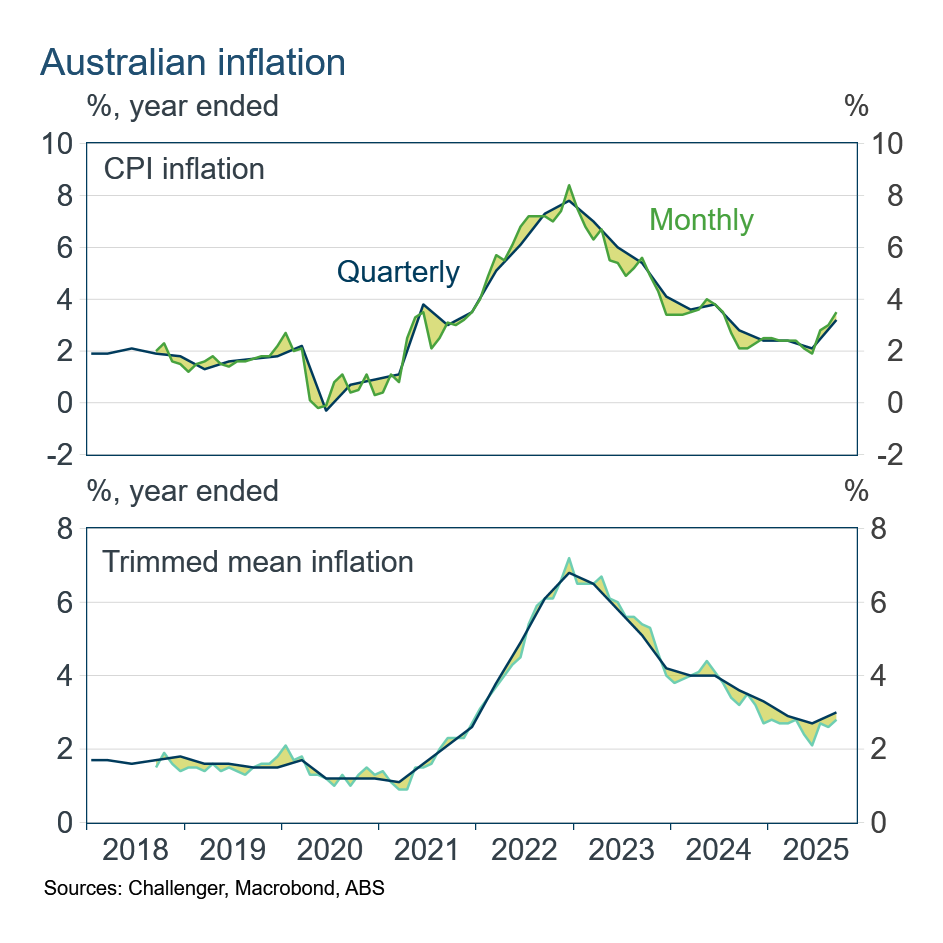

Inflation is much stronger than the RBA and financial markets expected, and that takes off the table any chance of a rate cut this year. The current outlook suggests rates could remain unchanged until the middle of next year.

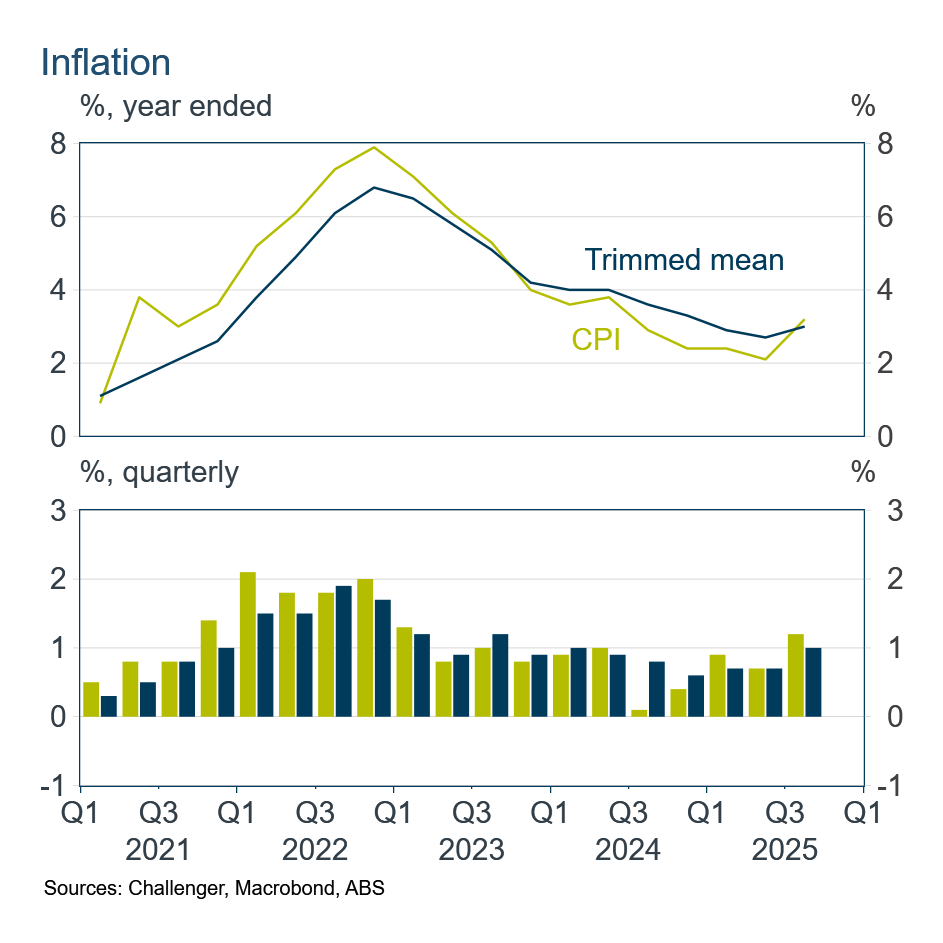

Inflation was 1.3% in the September quarter, and 3.2% over the year. That’s a hot reading. More alarming was trimmed mean inflation – which excludes volatile price movements and so is the RBA preferred measure of price pressures – which was 1.0% in the quarter and 3.0% over the year. The RBA’s most recent forecasts in August had this pencilled in for 0.6% in the quarter. The Governor was asked the other night what would be a significant miss; this is undoubtedly a very big miss. The path for inflation returning to the RBA’s target of 2.5% was never going to be smooth, but this is a big bump.

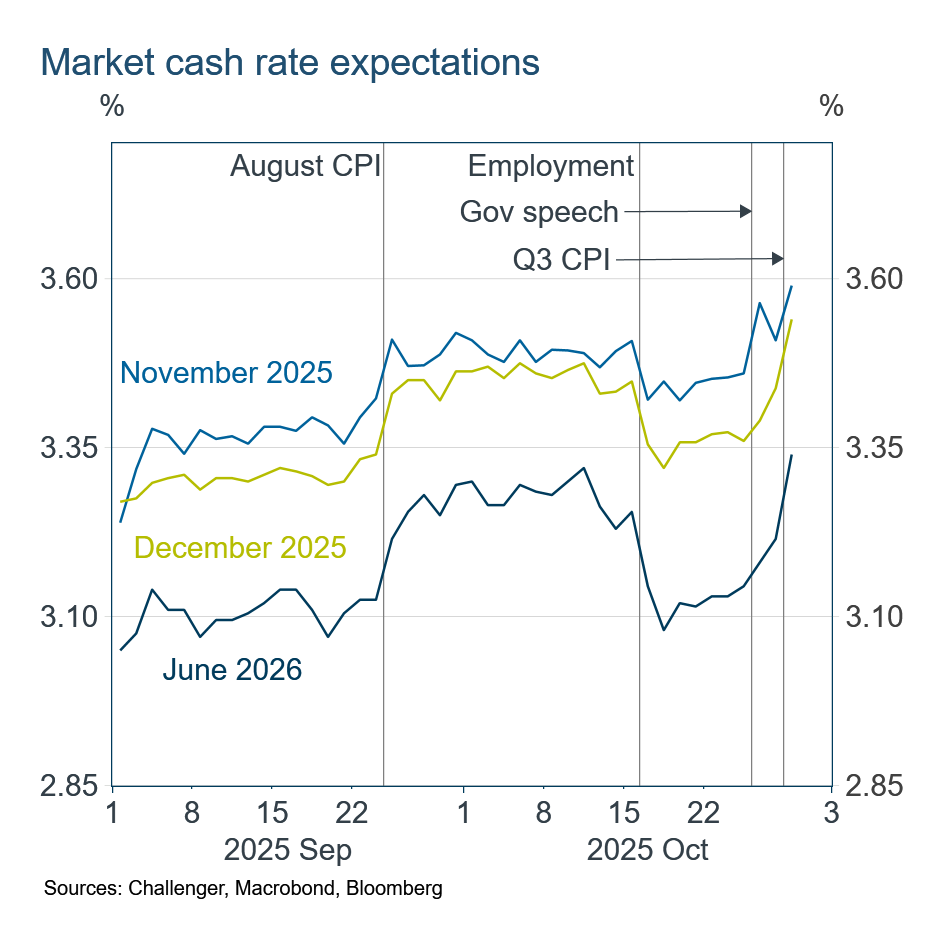

Over the past five weeks there have been some wild swings in the market’s pricing for the future cash rate. The stronger than expected August monthly CPI saw the expected future cash rate jump higher, with the market reducing its assessment of the likelihood of a November cut. Expectations for the cash rate then decreased with the tick up in unemployment rate to 4.5%, before reversing with the Governor’s ‘fireside chat’ where she struck a cautious tone about how quickly the RBA was squeezing excess inflation out of the system.

The keenly awaited September quarter inflation data validated the Governor’s caution, but even the RBA will have been surprised and disappointed by this number. However, even after the hot inflation data the market is pricing around a one quarter chance of a cut in December. That is overdone.

The RBA will have the new monthly CPI (which will now cover all components, unlike the monthly CPI indicator up to now) for its December meeting. But the RBA has said it will still put greater weight on the quarterly CPI for some time as it learns the behaviour of the monthly CPI. So even a weak October monthly CPI (released late November) won’t be enough to convince the RBA that inflation pressure has eased by the time of its December meeting.

Part of the challenge for the RBA has been that the monthly CPI indicator has been an imperfect predictor of quarterly CPI inflation. While monthly CPI has been more volatile than quarterly CPI, the monthly trimmed mean has been close to useless. It has been consistently lower than the quarterly trimmed mean over the past year. That’s why the future for rates was depending on the quarterly CPI release.

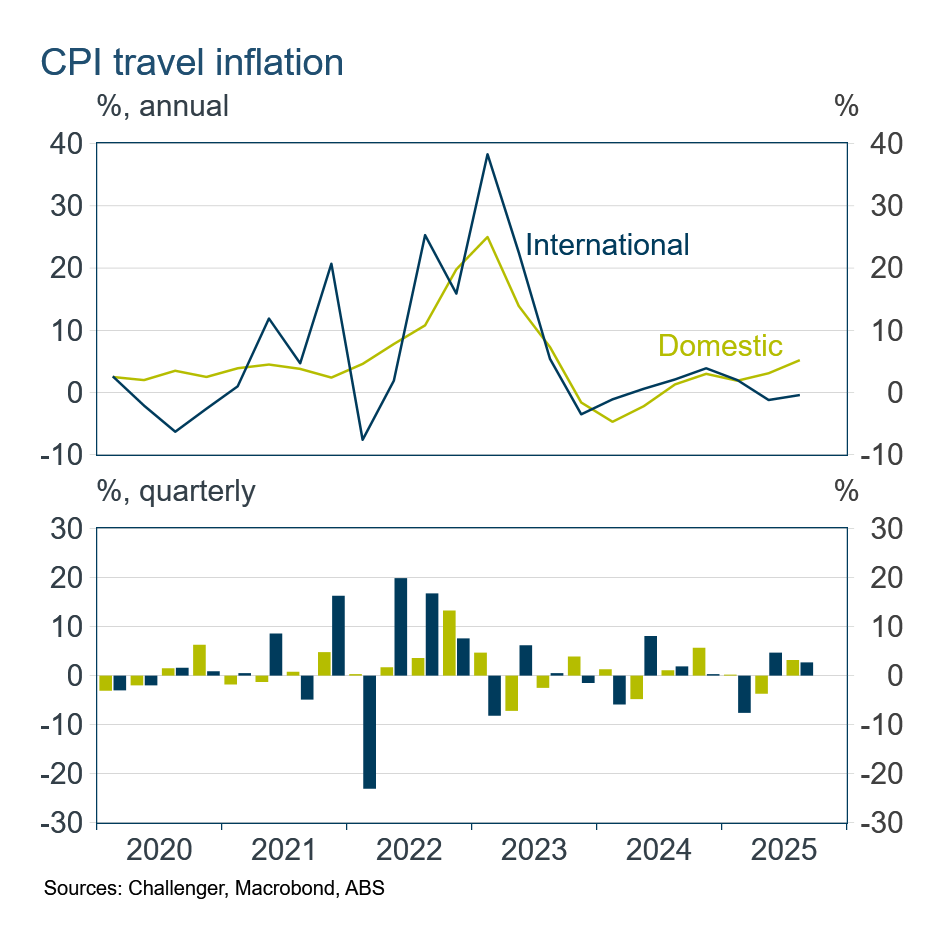

Inflation was strong across the board, including in the closely watched market services components (which are more determined by the balance of supply and demand). Domestic travel came in at 3.2% in the quarter, with international travel at 2.9%. The cost of travel remains significantly above its pre-pandemic trend.

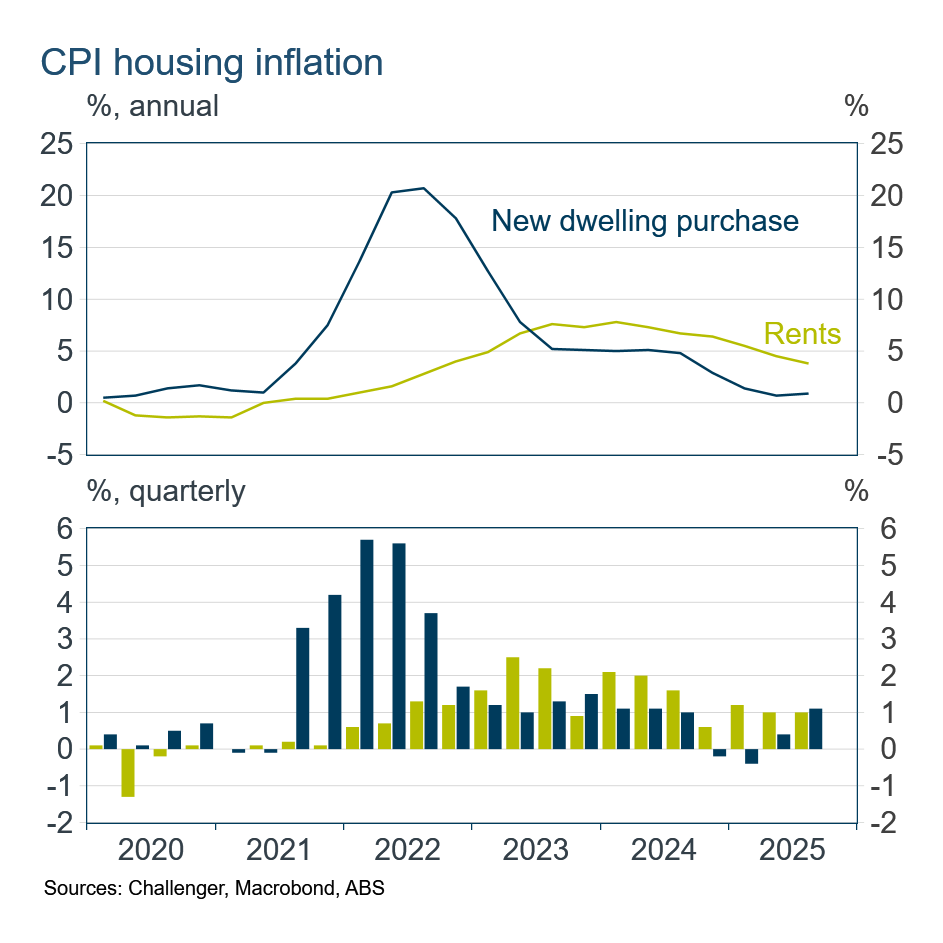

The RBA had been comforted by the easing in rent inflation up to the middle of the year, however that has now stalled. Rents increased 1% in the quarter, the same as in the previous quarter. Alarmingly, price increases for new dwellings, which reflect material prices but also the cost of tradespeople, have been picking up speed.

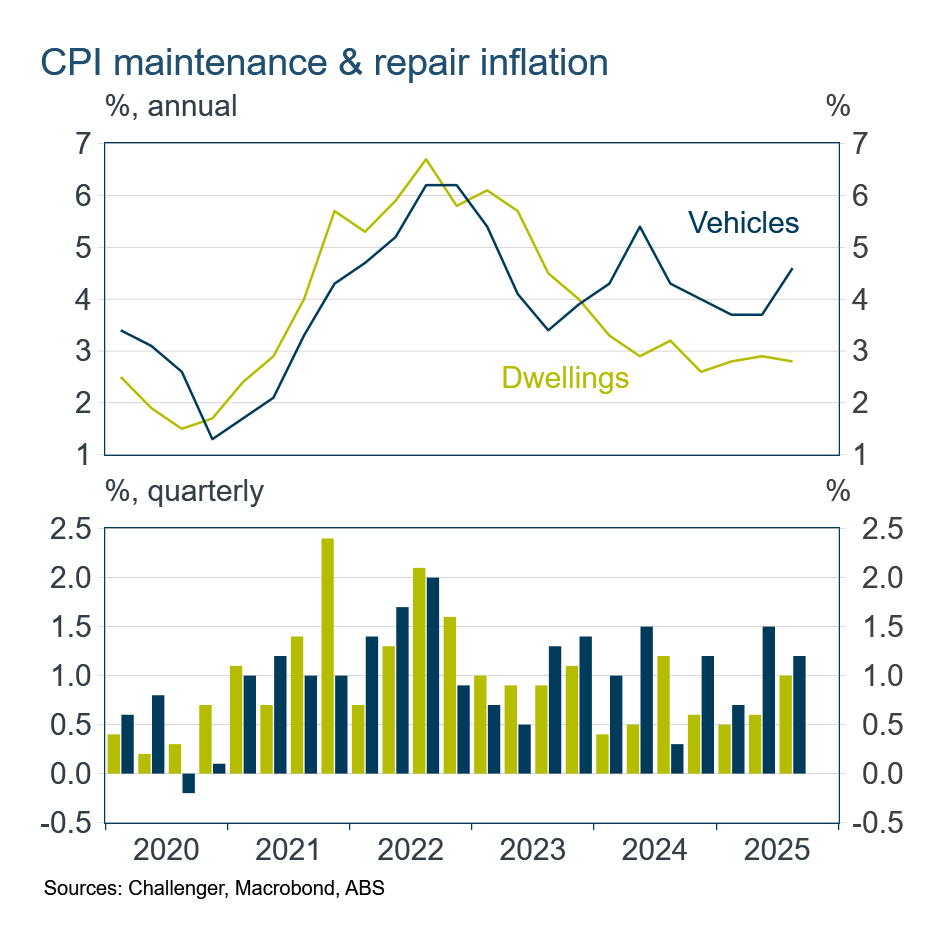

Another indicator of the impact of labour costs on inflation comes in the cost of maintenance and repair of vehicles and dwellings. Quarterly inflation rates of 1% and above highlight the pressure from wages.

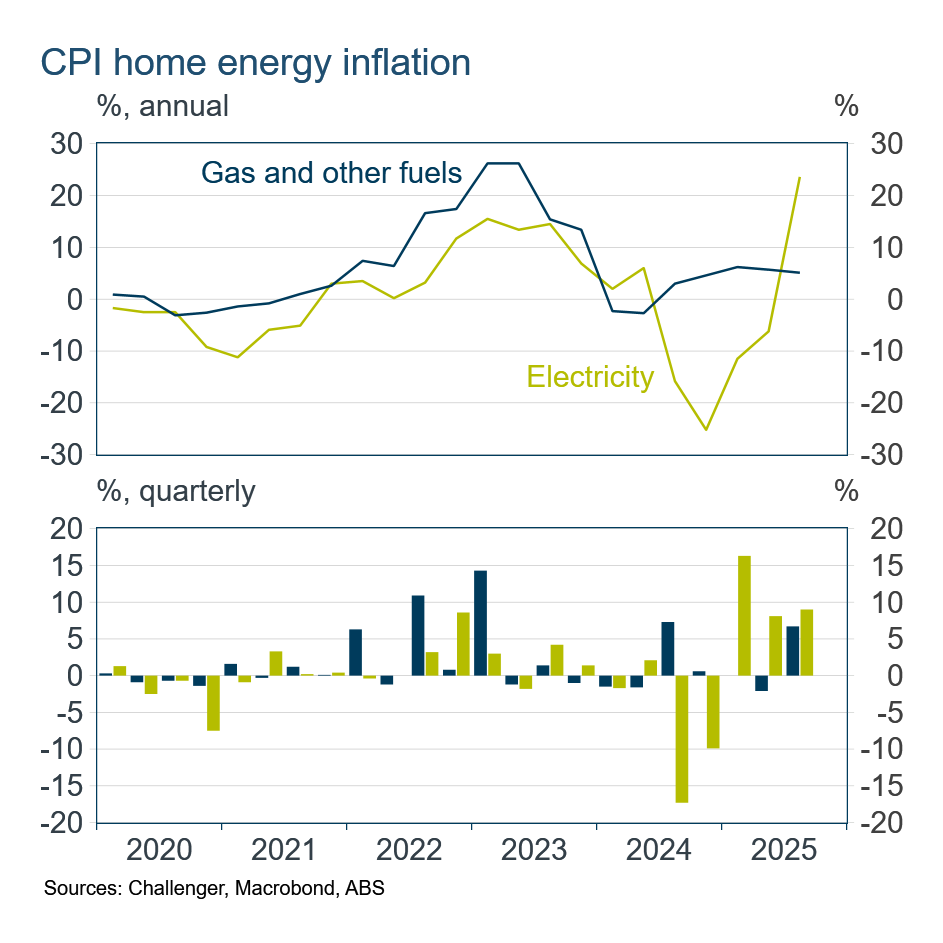

Electricity prices have been a big swing factor for inflation. Electricity rebates provided by the Australian and state governments saw electricity prices fall 25% last year. With state government rebates no longer holding down the price, the electricity price in the CPI has bounced back, increasing 24% over the year. As the final rebates roll off, electricity inflation will remain strong.

There’s no doubt inflation is hot, and that pushes out any further rate cuts, well into next year.