Trump’s tariff cuts: impact on inflation, trade, and Australia’s exports

Subscribe to Macro Musing

To stay up to date on the latest economic insights, subscribe to Macro Musing on LinkedIn.

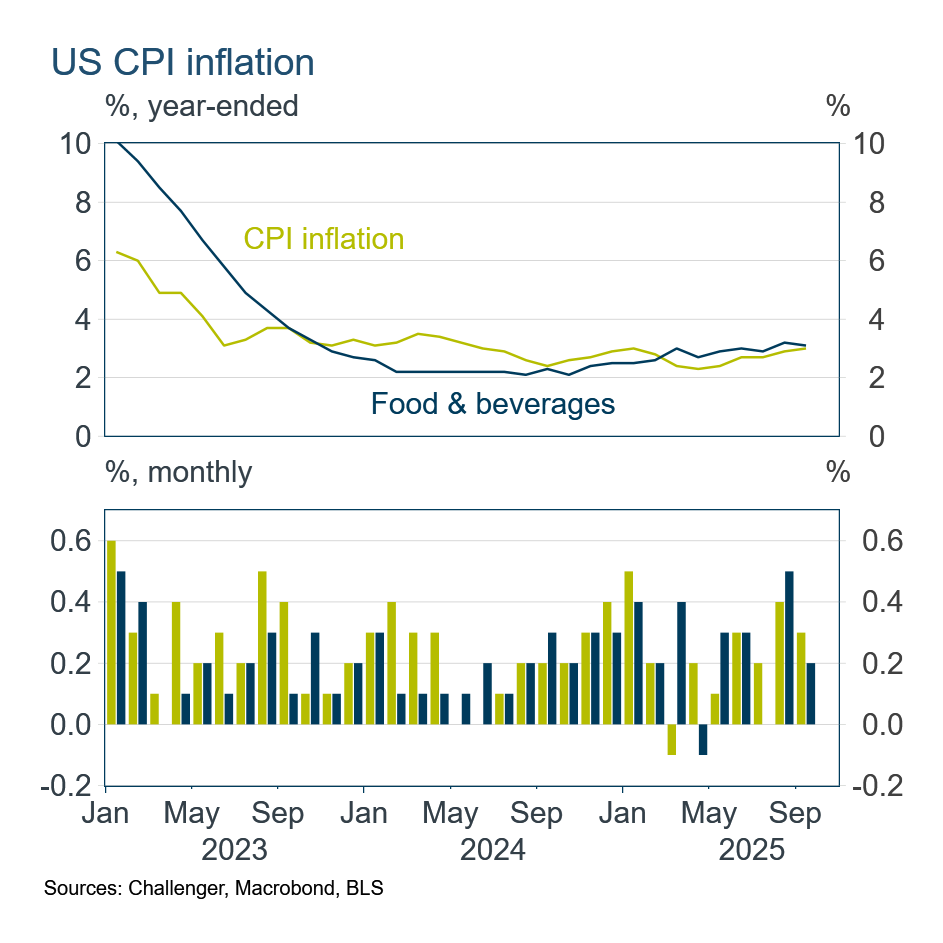

This week President Trump announced a reduction in tariffs on a range of food items (including coffee, tea, beef and some fruits) to lower inflation. While President Trump has previously suggested tariffs don’t increase domestic prices, this tariff reduction should marginally reduce inflation. However, tariffs continue to distort trade patterns.

While food inflation has been running a bit stronger than total CPI inflation, it has not picked up as much this year. Over the year to September, food prices increased 3.1%, only a touch higher than aggregate inflation of 3.0%. Food prices aren’t the smoking gun for rising US inflation.

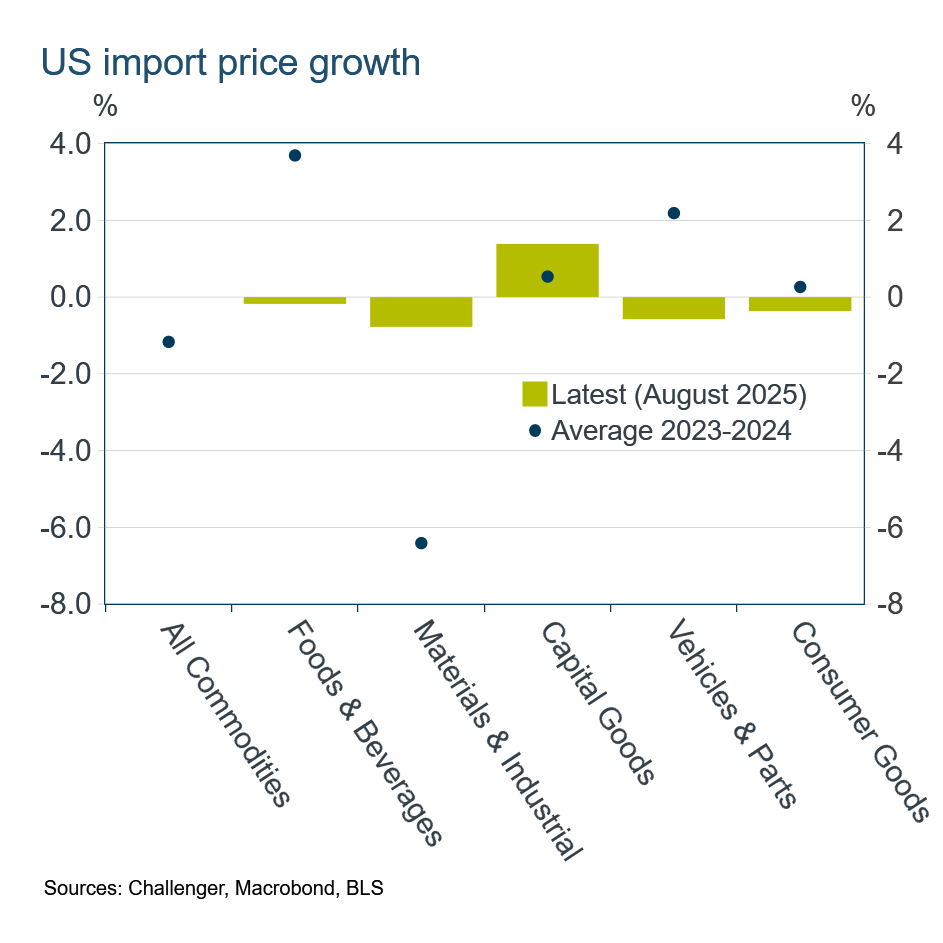

Indeed, US food import prices abstracting from the impact of tariffs actually fell over the year to August (the latest available data given the US government shutdown). This is well below the nearly 4% average annual increase in food import prices over 2023 to 2024. Only the capital goods category of imports has experienced higher prices over the past year.

Overall, evidence suggests tariffs have only marginally contributed to higher inflation as wholesalers and retailers have to date partly absorbed tariffs, and there has been a reduction in imports of those goods with higher tariffs. But the inflation impact of tariffs will grow as businesses begin to accept that tariffs will remain and so attempt to rebuild margins and inventories of goods imported before the imposition of tariffs are depleted.

Overall, goods import prices are unchanged over the past year (exclusive of the impact of tariffs), well below the rates of 10% and higher experienced in the 2021-2022 inflation surge. Lower global goods price inflation is helping to moderate the inflationary impact of tariffs.

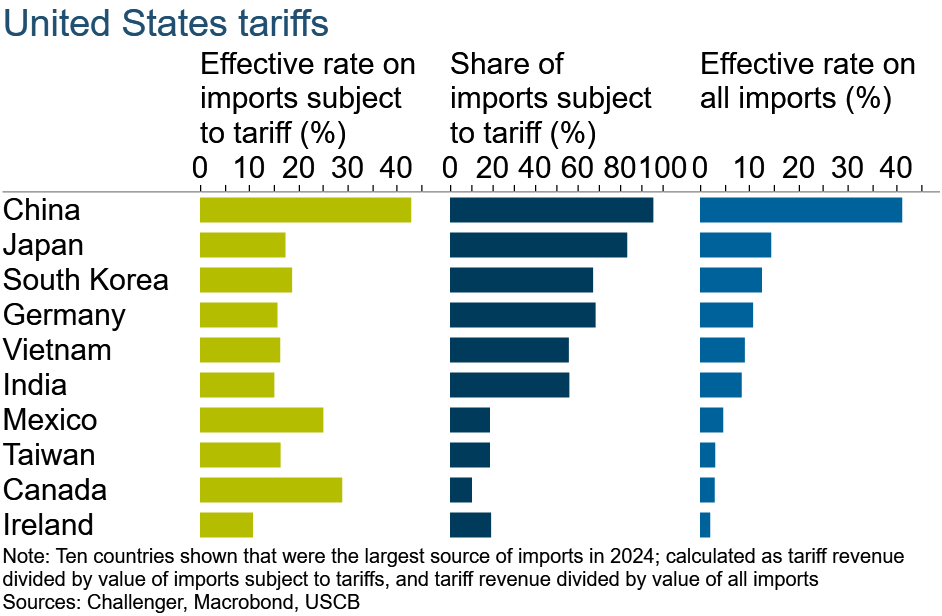

One reason that tariffs have had a muted impact is that not all US goods imports are subject to tariffs. This is particularly the case for countries with pre-existing free trade agreements with the United States, such as Canada and Mexico. For example, while the effective tariff rate on goods imports from Canada subject to tariffs is 29%, only 10% of goods imports from Canada are subject to tariffs as most are covered by the pre-existing free trade agreement (renegotiated by President Trump in his first term). The effective tariff rate over all Canadian imports is then just 3%.

At the other end of the spectrum is China, for which 96% of imports by value are subject to tariffs, making the effective tariff rate on imports from China just over 40%.

The United States has applied higher tariffs to some specific goods, for example steel, aluminium and cars. It has also applied so-called ‘reciprocal tariffs’ where the rates differ on individual countries. It is these reciprocal tariffs that are being challenged in the Supreme Court and an adverse ruling could force the US to refund the tariff revenue collected and reconsider how to legally impose these broad tariffs.

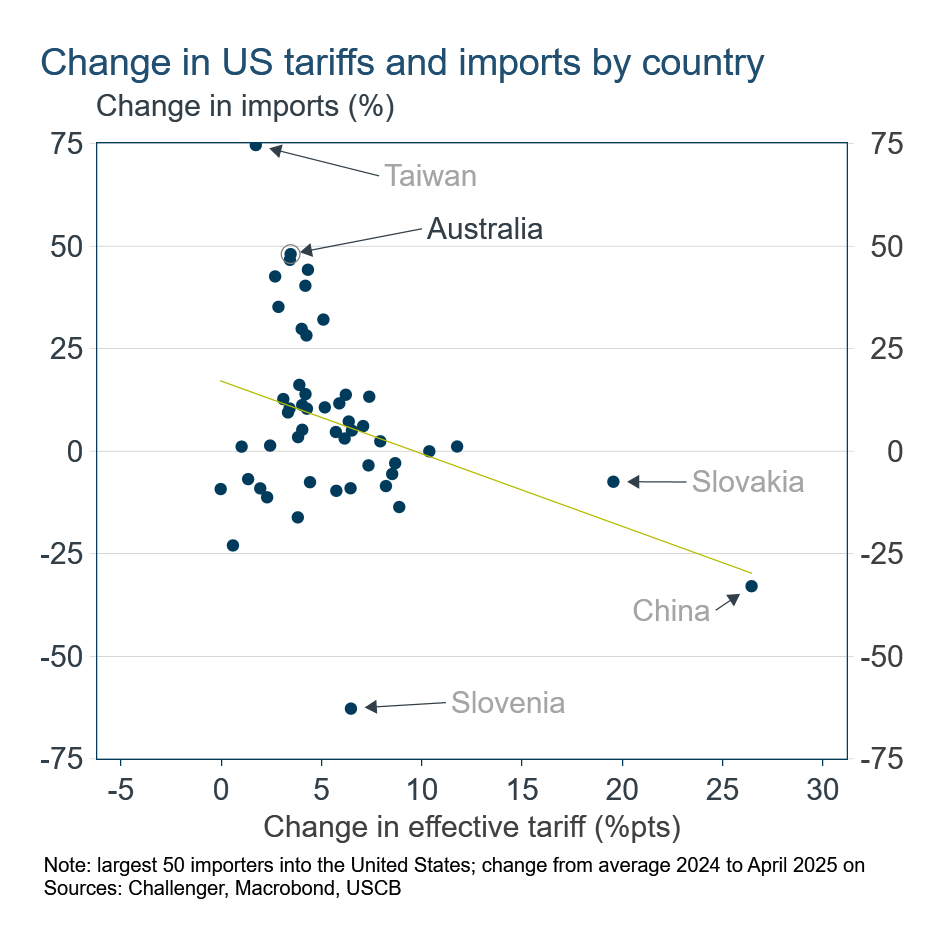

Because these reciprocal tariff rates differ by country they give countries with a relatively lower reciprocal tariff, such as Australia’s 10% rate, a comparative advantage. Indeed those countries with a smaller increase in their effective tariff have generally seen an increase in their exports.

A large share of Australia’s 50% surge in exports (following the imposition of tariffs) is a result of gold exports (which are not subject to any tariffs), but other exports, and in particular beef, have also increased significantly. A reduction in reciprocal tariffs applied to US beef imports will reduce the price advantage that Australian beef exporters have had relative to exports from other countries. However, the tariff reduction only applies to the ‘reciprocal tariff’ and so significantly beef exports from Brazil will still be subject to the additional 40% tariff applied to that country. That will mean a significant part of Australia’s price competitiveness for beef imports in the United States will remain.