Rising government yields, high debt and budget deficits risk a debt crisis

Subscribe to Macro Musing

To stay up to date on the latest economic insights, subscribe to Macro Musing on LinkedIn.

Unsustainable fiscal positions are pushing up the cost of borrowing for a number of governments threatening a fiscal doom loop. This follows significant increases in long-term yields after the pandemic as inflation picked up and central bank purchases of bonds were wound back.

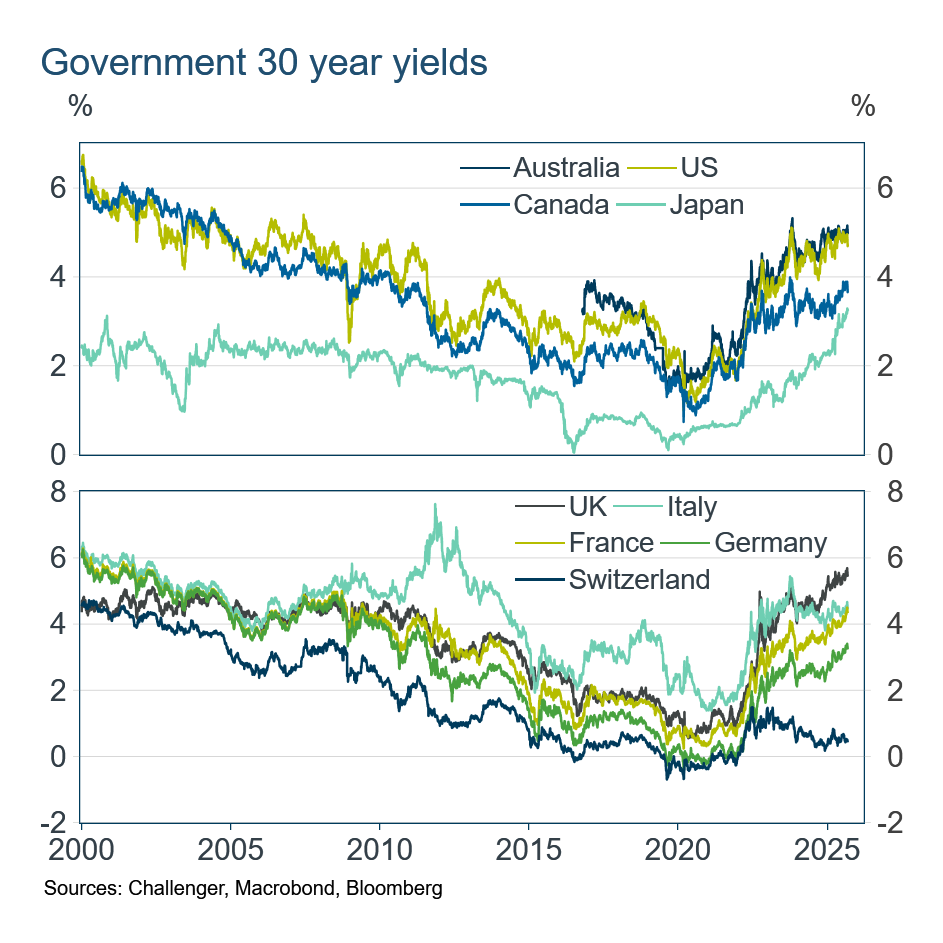

Yields on Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) have increased sharply, with inflation, to the highest rate since the Japanese Government first issued 30-year bonds in 1999.

UK yields have surged to their highest since 1998 as their fiscal position deteriorates and the Government faces internal revolt on measures to cut expenditure and/or increase revenue. UK yields are now 100 basis points higher than Italian yields, a remarkable situation given Italian yields were 400 basis points higher than UK yields in the European debt crisis in 2011. Indeed, yields on Italian bonds are only slightly above those on French bonds.

Perhaps surprisingly, Australian 30-year yields are slightly higher than US yields and are the second highest among the advanced economies, after UK yields, more than enough to compensate for its 0.5% higher inflation target.

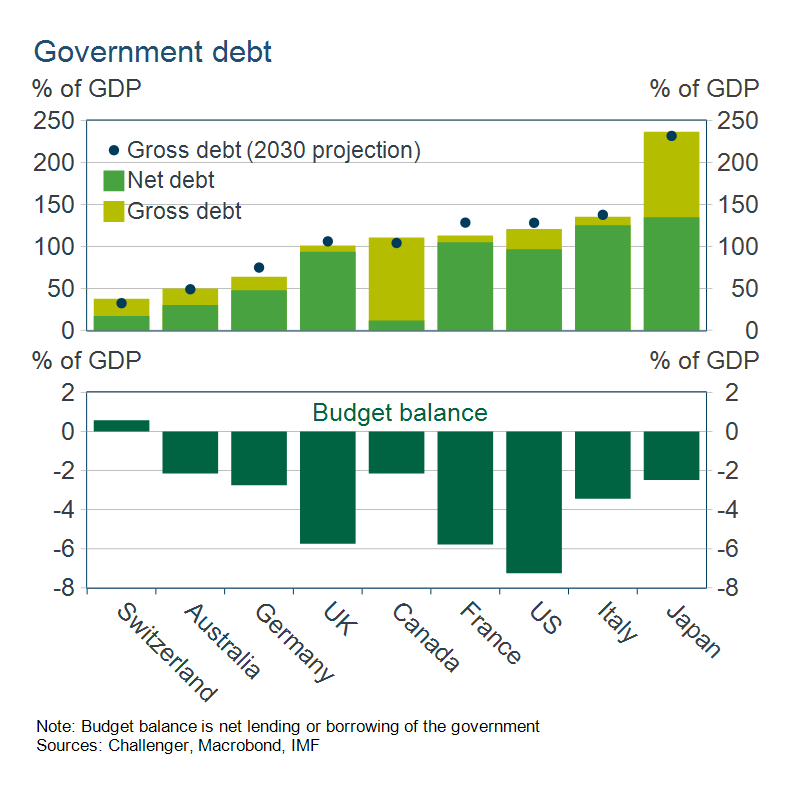

Governments’ fiscal positions explain much of the change in, and relativities of, long-term yields. The UK and France have high debt, around 100% of GDP, and large fiscal deficits, with net borrowing around 6% of GDP. While the Canadian government also has gross debt around 100% of GDP, it has significant financial assets, in particular large pension funds, and so its net debt is the lowest among these advanced economies.

Switzerland stands out for its yields having fallen in recent years. Switzerland’s stunningly low 30-year rate of less than 0.5% reflects its low debt, balanced budget, the central bank having cut its policy rate to zero, with an inflation rate just above zero.

The United States also has a large budget deficit adding to an already large government debt. While it’s 30-year yield is among the highest of these countries, it is perhaps surprising that it hasn’t increased more. For now the US’ exorbitant privilege to borrow cheaply lives on, but it would be surprising if investors don’t demand a higher risk premium with rising debt levels.

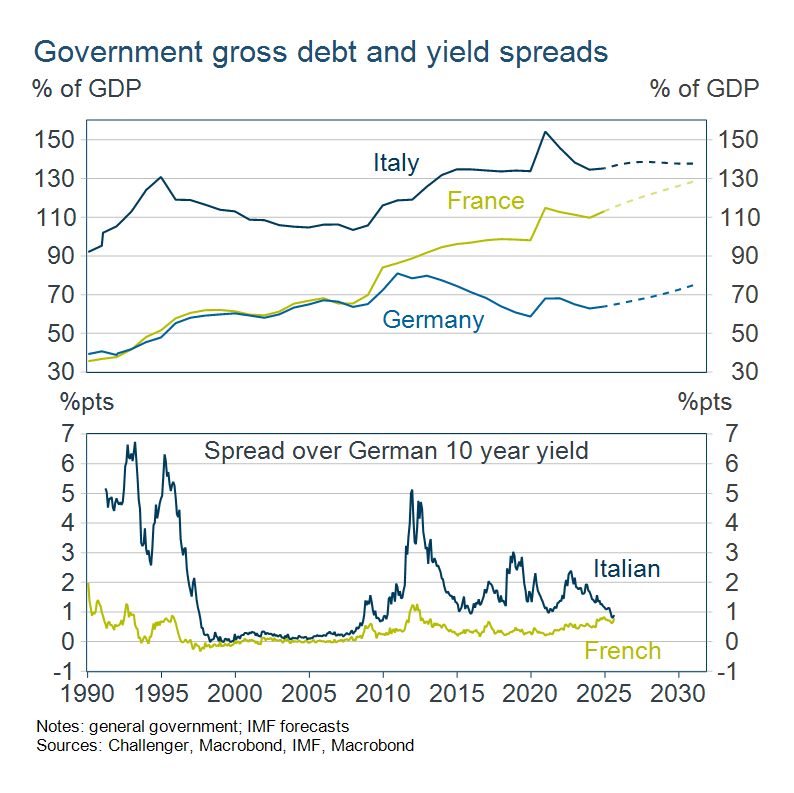

Changes in European fiscal positions and yields are particularly striking. Until the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), French government debt to GDP levels were similar to Germany’s. However, the French government did not match the fiscal discipline of Germany between the GFC and pandemic and its debt to GDP is projected to continue rising to be close to the level in Italy by 2030.

Given this, Italian debt is trading at similar spreads as French debt. In an environment where spreads are tight for even risky corporate debt, Italian debt has traded to substantially tighter spreads while French debt has only moved slightly wider. The stability of the Italian fiscal outlook coincides with the stability of its government. In contrast, since Giorgia Meloni was elected Italian Prime Minister, France has had five Prime Ministers adding to the challenges of reigning in its budget.

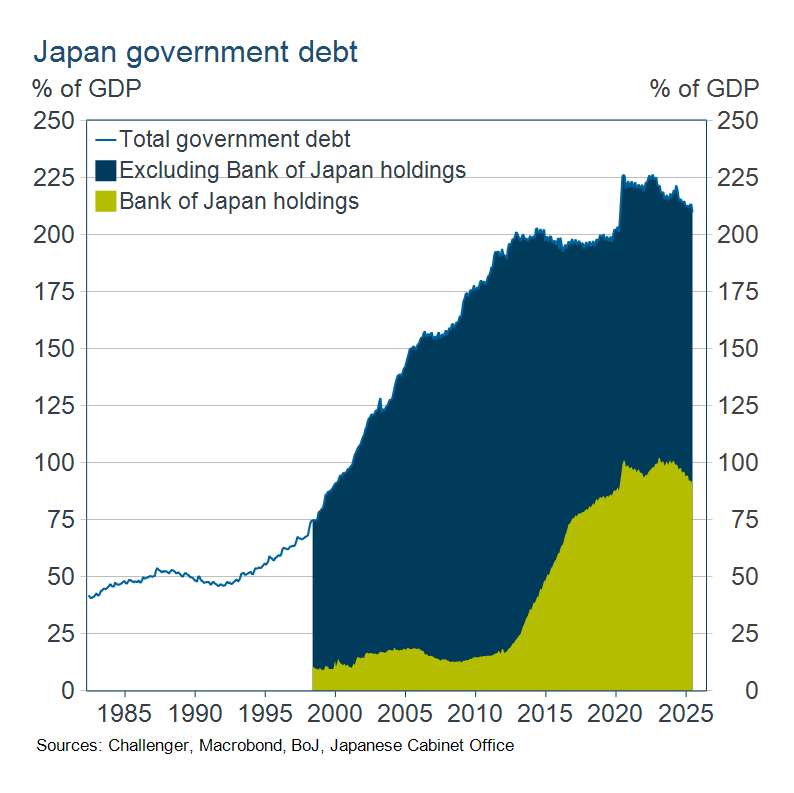

At first pass, it’s surprising that Japan hasn’t had a financial crisis given its gross debt to GDP of 240% of GDP. However, after years of substantial monetary stimulus through bond purchases, the Bank of Japan’s holdings of government debt amount to 90% of GDP. Overall, net Japanese government debt is still very high, at 135% of GDP. It is often noted that with around 90% of Japanese debt held domestically, Japan is less subject to a potential fiscal crisis from fleeing international investors. That might be true, but with yields rising sharply, the growing cost of financing that large debt increases the risk of a fiscal sustainability crisis.

Rising government yields in many advanced economies reflect increased risk given large budget deficits that are adding to already high debt levels. Given Australia’s relatively low debt and better (but still not great) budget position, Australia’s high 30-year yields, second highest among this group, seem to give a very good risk-adjusted return.