Protecting members from longevity risk: Part one

Thought Leadership

Benefits of pooling for retirement incomes

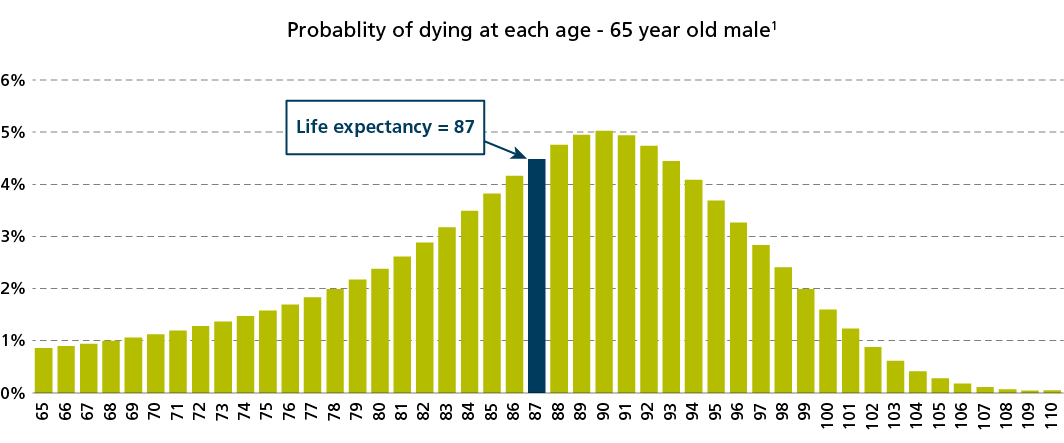

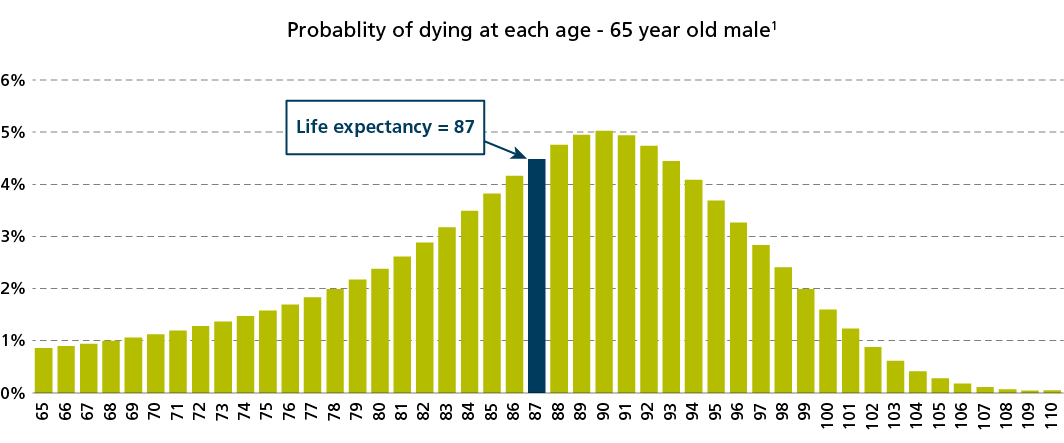

A feature of life expectancy is that over half the people of a certain age will live longer than their life expectancy. Retirees using these widely published figures as a reference point when planning how to spend their savings, are more likely than not to run out. The chart below shows how likely someone retiring today is to pass away at each age into the future.

More prudent retirees who plan for their savings to last longer than life expectancy can reduce the risk of outliving their savings, but this comes at the expense of a more frugal retirement. In the example above, our 65-year-old male has less than a 1 in 10 chance of living past age 97. However, if the retiree spread out his spending so that his savings lasted to age 97, the annual retirement income from his savings might be around 20% lower than if he’d planned for life expectancy.2 It is this uncertainty that makes planning how to spend your retirement savings so difficult.

There is a growing acceptance from super funds that current account-based retirement products, where members bear all the risks (including longevity risk), lead to poor outcomes for many members. With prompts from the government, forward-looking funds are considering retirement products that pay members an income for life.

Benefits of pooling

There are two forms of longevity risk. Systematic longevity risk is the potential for the population (or a particular cohort within it) to live longer (or shorter) than assumed and is linked to factors such as medical improvements and lifestyle changes. Idiosyncratic longevity risk relates to the fact that some people will live considerably longer than the average, and others shorter. Pooling a group of retirees of the same age, will tend to have a more reliable distribution of ages at death. As the pool gets larger, the distribution of lifespans around the mean is more predictable. Pooling retirees can significantly reduce idiosyncratic longevity risk.

The benefits of pooling can be passed on to retirees in a number of ways. A lifetime annuity is the classic example. Super funds can also provide lifetime income products by pooling together retirees’ capital through a product known as a group self-annuity (GSA). GSA’s don’t provide guarantees and don’t protect participants from systematic longevity risk. However, with enough members they can reduce the uncertainty for individual members by removing idiosyncratic longevity risk and provide an income stream for life.

The benefit payments made to members in a GSA are determined based on assumptions about how long members will live. Benefit payments are then adjusted to the extent that the actual experience of members differs from those assumptions.

To take a simplified example, consider a GSA with 500 male members, all 70 years old. It can be expected that 493 would survive to the following year, and the projected payment in the following year are based on this playing out.3 If fewer members pass away, then the benefit payments going forward are reduced, as benefits are being payed to more members than assumed. The greater the deviation from the assumed number of survivors, the larger the adjustment that is needed to members’ benefits. This is why the size of the pool is important. The larger the pool of members, the less likely it is that assumptions will be deviated from, as a proportion of the total membership. Adjustments to members’ benefits due to mortality experience are therefore likely to be smaller for larger pools of members.

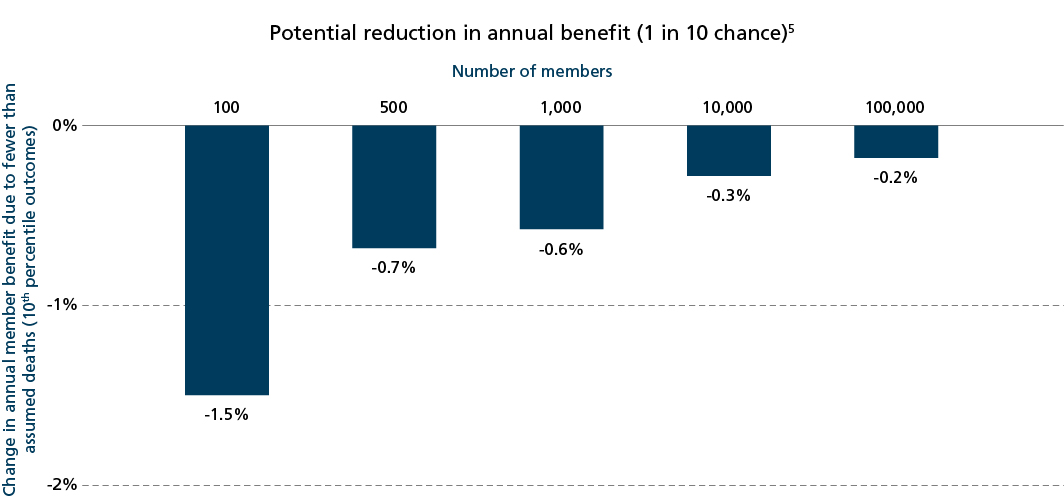

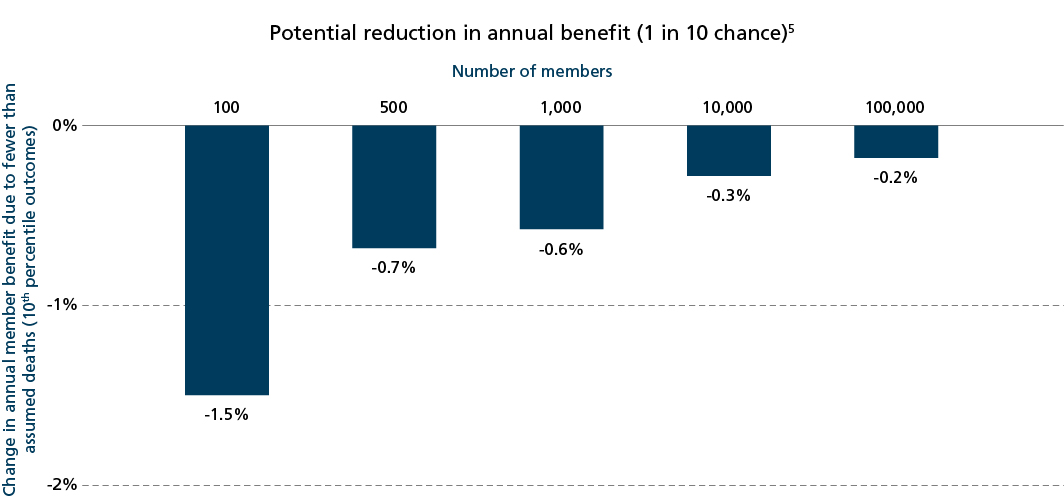

The chart below shows the impact on members’ benefits when fewer members than assumed die in a particular year. It considers a hypothetical GSA where benefit payments are adjusted each year in line with experience and looks at the reduction the payments members receive year-on-year as a result of mortality experience differing from the assumptions. It assumes all other experience, such as investment returns, is in line with what was assumed when payments were set. For example, for the GSA product with 500 members, there is around a 1 in 10 chance that the actual number of survivors is 496 rather than 493. With more survivors the annual payment for each member would need to be reduced by 0.7% in the following year.4 In smaller pools, it only takes a few more survivors in a given year to drive a material change in benefits for all members.

Consistent with other research6, this suggests that a pool of at least 10,000 members would be preferable to reduce the risk of a member’s payments falling significantly from one year to the next due to mortality experience. Divergence from assumptions over longer periods can potentially see greater falls in member benefits. This also doesn’t consider the systematic longevity risk that arises if the assumptions are incorrect.

Of course, members of super funds aren’t all the same age when they retire, and their health and longevity traits will vary widely too. This heterogeneity can lead to greater volatility in payments.

Careful consideration will be needed of how benefit adjustments due to mortality experience will be communicated to members. For example, how might members feel if it is communicated that their benefits have increased because a greater number of their fellow members have passed away?

Alternative approaches to passing on volatility to members

Rather than letting members bear all the volatility of benefit payments that can result from a pool that is too small, super funds can look at other ways to manage that risk. Options include:

Conclusion

Pooled retirement products can significantly reduce or remove idiosyncratic longevity risk, providing better outcomes for members than current account-based products. However, to be effective, pooled products need sufficient scale and it can take time to get there.

Rather than go it alone, super funds can still offer their members the benefits of these products by partnering with a life insurer to outsource some of the risk and provide members with a more certain lifetime income.

It’s important to consider longevity solutions when designing retirement solutions for members. Our latest paper ‘Guided choice retirement solutions’ explores ways to think about and design solutions in the best interest of members using your chosen longevity product.

More prudent retirees who plan for their savings to last longer than life expectancy can reduce the risk of outliving their savings, but this comes at the expense of a more frugal retirement. In the example above, our 65-year-old male has less than a 1 in 10 chance of living past age 97. However, if the retiree spread out his spending so that his savings lasted to age 97, the annual retirement income from his savings might be around 20% lower than if he’d planned for life expectancy.2 It is this uncertainty that makes planning how to spend your retirement savings so difficult.

There is a growing acceptance from super funds that current account-based retirement products, where members bear all the risks (including longevity risk), lead to poor outcomes for many members. With prompts from the government, forward-looking funds are considering retirement products that pay members an income for life.

Benefits of pooling

There are two forms of longevity risk. Systematic longevity risk is the potential for the population (or a particular cohort within it) to live longer (or shorter) than assumed and is linked to factors such as medical improvements and lifestyle changes. Idiosyncratic longevity risk relates to the fact that some people will live considerably longer than the average, and others shorter. Pooling a group of retirees of the same age, will tend to have a more reliable distribution of ages at death. As the pool gets larger, the distribution of lifespans around the mean is more predictable. Pooling retirees can significantly reduce idiosyncratic longevity risk.

The benefits of pooling can be passed on to retirees in a number of ways. A lifetime annuity is the classic example. Super funds can also provide lifetime income products by pooling together retirees’ capital through a product known as a group self-annuity (GSA). GSA’s don’t provide guarantees and don’t protect participants from systematic longevity risk. However, with enough members they can reduce the uncertainty for individual members by removing idiosyncratic longevity risk and provide an income stream for life.

How many members make a pool?

To understand whether a pooled product is viable for a particular super fund, it is necessary to know what size of pool is needed to reduce the longevity risk for members.

To understand whether a pooled product is viable for a particular super fund, it is necessary to know what size of pool is needed to reduce the longevity risk for members.

The benefit payments made to members in a GSA are determined based on assumptions about how long members will live. Benefit payments are then adjusted to the extent that the actual experience of members differs from those assumptions.

To take a simplified example, consider a GSA with 500 male members, all 70 years old. It can be expected that 493 would survive to the following year, and the projected payment in the following year are based on this playing out.3 If fewer members pass away, then the benefit payments going forward are reduced, as benefits are being payed to more members than assumed. The greater the deviation from the assumed number of survivors, the larger the adjustment that is needed to members’ benefits. This is why the size of the pool is important. The larger the pool of members, the less likely it is that assumptions will be deviated from, as a proportion of the total membership. Adjustments to members’ benefits due to mortality experience are therefore likely to be smaller for larger pools of members.

The chart below shows the impact on members’ benefits when fewer members than assumed die in a particular year. It considers a hypothetical GSA where benefit payments are adjusted each year in line with experience and looks at the reduction the payments members receive year-on-year as a result of mortality experience differing from the assumptions. It assumes all other experience, such as investment returns, is in line with what was assumed when payments were set. For example, for the GSA product with 500 members, there is around a 1 in 10 chance that the actual number of survivors is 496 rather than 493. With more survivors the annual payment for each member would need to be reduced by 0.7% in the following year.4 In smaller pools, it only takes a few more survivors in a given year to drive a material change in benefits for all members.

Consistent with other research6, this suggests that a pool of at least 10,000 members would be preferable to reduce the risk of a member’s payments falling significantly from one year to the next due to mortality experience. Divergence from assumptions over longer periods can potentially see greater falls in member benefits. This also doesn’t consider the systematic longevity risk that arises if the assumptions are incorrect.

Of course, members of super funds aren’t all the same age when they retire, and their health and longevity traits will vary widely too. This heterogeneity can lead to greater volatility in payments.

Careful consideration will be needed of how benefit adjustments due to mortality experience will be communicated to members. For example, how might members feel if it is communicated that their benefits have increased because a greater number of their fellow members have passed away?

Establishing and winding down

For super funds that are confident of reaching the scale needed to operate a pooled retirement product, a second issue is the time needed to get there. If mortality experience is passed on continuously (e.g. in annual benefit indexation) to members, then it is likely they will experience volatile benefit payments in the first few years of the product’s life.

For super funds that are confident of reaching the scale needed to operate a pooled retirement product, a second issue is the time needed to get there. If mortality experience is passed on continuously (e.g. in annual benefit indexation) to members, then it is likely they will experience volatile benefit payments in the first few years of the product’s life.

Alternative approaches to passing on volatility to members

Rather than letting members bear all the volatility of benefit payments that can result from a pool that is too small, super funds can look at other ways to manage that risk. Options include:

- Reserves

Like a traditional defined benefit fund, super funds could hold reserves to support a pooled product, either permanently or until the pooled product reaches scale. The reserves can be used to smooth benefit payments and reduce the volatility for members.

Equity for other classes of members requires that reserves are established from part of the pooled product members’ initial contributed capital. This will necessarily reduce the benefit payments members receive, at least initially. The reserves will need to be managed which can add costs. Added complexity can reduce the transparency to members, making communicating with them more difficult.

- Insurance

It is also possible for super funds to insure longevity risk to provide greater certainty for members. In a longevity swap a counterparty takes on this risk for the fund, for a cost, to remove members’ exposure to longevity risk. The super fund has certainty over how long benefit payments will need to be paid to members while the insurer picks up the tab if members live longer than expected. Generally, the insurance ‘trues up’ against mortality experience each year allowing the super fund to provide more stable benefit payments. As with all insurance, longevity swaps have a cost, the trade-off coming in the form of slightly lower expected returns to members over the long term.

Conclusion

Pooled retirement products can significantly reduce or remove idiosyncratic longevity risk, providing better outcomes for members than current account-based products. However, to be effective, pooled products need sufficient scale and it can take time to get there.

Rather than go it alone, super funds can still offer their members the benefits of these products by partnering with a life insurer to outsource some of the risk and provide members with a more certain lifetime income.

It’s important to consider longevity solutions when designing retirement solutions for members. Our latest paper ‘Guided choice retirement solutions’ explores ways to think about and design solutions in the best interest of members using your chosen longevity product.